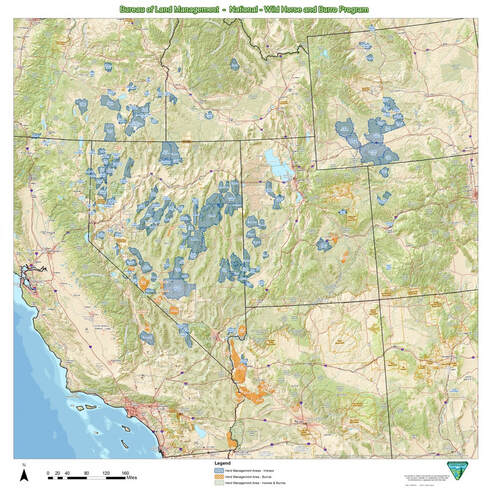

In response to public concerns regarding the status and treatment of free-roaming equids (horses and burros), in 1971, Congress passed the Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act (WHBA). The WHBA gave these animals protection against capture, branding, harrassment or death from any private individual or group. Additionally, the act gave the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service the statutory obligation to manage and protect feral equids in designated herd management areas (HMAs, Public Law 92-195). The intent of the WHBA was to ensure healthy populations of free-roaming equids in ecological balance with other multiple-uses. Other uses include wildlife, livestock, wilderness, and recreation considerations. In 2018, the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service determined a suitable number of free-roaming equids was 26,690 animals on the 29.4 million acres designated HMAs on public land across 10 western states. This number was based on the amount of food (grasses) and water available on public lands. As of 1 March 2019, the Bureau of Land Management estimated that there were 88,090 wild horses and burros inhabiting designated HMAs, surrounding herd areas, and other private and public lands.

To return the free-roaming horse and burro populations to a sustainable level based on 2019 rangeland health, the Bureau of Land Management and U. S. Forest Service would have needed to remove more than 65,000 animals from the HMAs.

Follow this link to watch a short video about free-roaming horses in the U.S.

To return the free-roaming horse and burro populations to a sustainable level based on 2019 rangeland health, the Bureau of Land Management and U. S. Forest Service would have needed to remove more than 65,000 animals from the HMAs.

Follow this link to watch a short video about free-roaming horses in the U.S.

Horses in an off-range holding facility.

Horses in an off-range holding facility.

Tools in the Toolbox

Current management practices that the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service can use to manage horse and burro populations include adoption, immuno-contraception (birth control), and removing animals from the HMAs and holding them in long term facilities. Those animals in long term facilities can then be adopted or sold to private U. S. citizens. While authorized to euthanize free-roaming horses and burros, the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service do not kill animals unless the animals are starving, dehydrated, or injured beyond recovery.

There are currently approximately 50,000 horses held in long-term captive facilities, where they can be adopted, sold, or live out the rest of their lives until they die of natural causes. This costs about $50 million every year to provide for the horses and maintain the holding facilities. Over the past five years, an average of about 2,500 horses have been adopted through the Bureau of Land Management’s adoption services. However, demand to adopt a horse or burro is decreasing while the number of horses needing to be adopted is increasing.

Immuno-contraception (birth control), usually through injections, have been tested and proven effective in reducing population growth rates. Injecting free-roaming horses and burros with contraceptives requires capturing free-roaming horses and burros and directly injecting them with a dose of the birth control. The injections cost about $500 per dose, last about one year, and have variable effectiveness of about 30-70% reduction of birth rate. This method will reduce the number of new horses on rangelands, but doesn't solve the problem of what to do with the over-population of free-roaming horses and burros that live on rangelands right now.

The Concern

Without more active management to reduce growth rates on public rangelands the free-roaming horse population could exceed 160,000 by 2025. At this population level, scientists and managers expect more free-roaming horses and burros will die from dehydration and starvation, due to lack of available resources on the landscape. Furthermore, without more active management, the negative impacts of free-roaming horses and burros to native wildlife and rangeland habitat will become irreversible.

|

|

What are Free-roaming Horses?In this video we discuss the status of free-roaming horses on western public lands in the U.S.

|

|

|

Free-Roaming Horses and WildlifeDid you know that horses are the only ungulate (hooved) in North America that has both top and bottom front teeth? Watch this video to discover how horses different from native North America wildlife, and how these differences can cause conflicts with wildlife conservation.

|

|

|

Free Roaming Horses Interact with Livestock, Too.Horses in North America aren't managed like other 'wildlife', but they aren't managed like 'cattle' or 'livestock' either. This presents some challenges to management. Watch this video to discover why we are concerned about managing free-roaming horses together with livestock and cattle.

|

Surveying the Public

Managing a federal resource, such as horses, requires the input of US citizens (P.L. 91-190). As one can imagine, the opinions on how to control horse populations differs greatly among regions of the US. In 1982, the National Research Council suggested that control strategies for horse populations must be responsive to public attitudes; a successful program cannot be based solely on biological or economic considerations (National Research Council, 1982). Public views of free-roaming horses range from regarding them as symbols of grace and courage, to that of an invasive species that competes with agriculture and wildlife (Scasta, 2018). In a study of human attitudes toward animals, Kellert (1984) found that horses were the second-most liked animals, behind the domestic dog. The most famous herd in Utah, the Onaqui Mountain herd in Tooele County, is advertised as a popular tourist attraction (wildhorsetourist.com). Meanwhile, horse herds in Millard, Beaver, and Iron County, Utah annually create conflicts for livestock producers and wildlife managers.

Several National Research Council reports (1980, 1982, 2013) highlight the need for research into the social context of horse management, particularly studies that evaluate what aspects of horse management are supported by the public. The information gained from such inquiries could be incorporated into methods to manage horses that also engage public stakeholders. Once decision makers (i.e. public land management agencies, state and local government representatives) understand the different levels of knowledge and opinions of public land management, horses, and horse management options, they can begin to strategically engage a diversity of backgrounds and viewpoints toward creating a management plan that would be supported by most of the public (National Research Council, 2013).

In 2019, the Cooperative Extension System and Agricultural Experiment Stations in Utah and Nevada initiated a Rapid Response Team to focus on free-roaming horse and burro management. This team is made up of specialists from 5 western states that study free-roaming horse biology, ecology, and management, rangeland ecology, and human-wildlife conflict management. The goal of the team is to provide service and momentum to aid the Bureau of Land Management and the US Forest Service in creating a successful free-roaming horse management program for the future. A subcommittee was formed to create a national public survey to gauge the public’s knowledge and opinions of wild horses. Members of the State of Utah, the Bureau of Land Management Wild Horse and Burro Program, and the US Forest Service regional ranger, and scientists involved in studying free-roaming horses reviewed and supported the survey prior to its launch.

Several National Research Council reports (1980, 1982, 2013) highlight the need for research into the social context of horse management, particularly studies that evaluate what aspects of horse management are supported by the public. The information gained from such inquiries could be incorporated into methods to manage horses that also engage public stakeholders. Once decision makers (i.e. public land management agencies, state and local government representatives) understand the different levels of knowledge and opinions of public land management, horses, and horse management options, they can begin to strategically engage a diversity of backgrounds and viewpoints toward creating a management plan that would be supported by most of the public (National Research Council, 2013).

In 2019, the Cooperative Extension System and Agricultural Experiment Stations in Utah and Nevada initiated a Rapid Response Team to focus on free-roaming horse and burro management. This team is made up of specialists from 5 western states that study free-roaming horse biology, ecology, and management, rangeland ecology, and human-wildlife conflict management. The goal of the team is to provide service and momentum to aid the Bureau of Land Management and the US Forest Service in creating a successful free-roaming horse management program for the future. A subcommittee was formed to create a national public survey to gauge the public’s knowledge and opinions of wild horses. Members of the State of Utah, the Bureau of Land Management Wild Horse and Burro Program, and the US Forest Service regional ranger, and scientists involved in studying free-roaming horses reviewed and supported the survey prior to its launch.

Scope of Work

The study consisted of an online survey administered by Qualtrics. This survey was stratified to evenly sample the national public by the following metrics: income, gender, age, and region of the US. We stratified the nation by Midwest (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, Wisconsin), Northeast (Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont), Southeast (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, West Virginia), Southwest (Arizona, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Texas), and West (California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, Wyoming). Our goal was 200 respondents in each of these regions, with an even distribution among gender, income, and age.

Qualtrics conducted the survey via email and tracked respondents until we acquired the indicated distribution and even stratification. As they acquired responses, they checked them for quality. Responses that took less than 5 minutes to answer, where the respondent selected the same response throughout, or survey were incomplete were rejected. Once we had our quota of respondents we closed the survey.

Survey Instrument

We created 60 questions on the following topics: Environmental attitudes, free-roaming horse biology and ecology, public land management policy, free-roaming horse management options, and rangeland ecology and management. We created questions to test the public’s knowledge of free-roaming horse biology, ecology and status in the US, and current public land management strategies. We also created questions to collect public opinion of free-roaming horse management strategies, including lethal and non-lethal options, and the economics of these strategies. All knowledge and opinion questions were presented in a multiple-choice format and required. Demographic questions were presented in multiple-choice format but not required. For this article we present the analysis of the public knowledge questions.

Survey Analysis

We used a combination of descriptive statistics and chi-square measures of associations for an analysis of the results. Within SPSS (IBM 2020), we used the Crosstabs analysis to conduct the chi-square measures of associations. We analyzed pair-wise association between each question and age, gender, region of the U. S., and income. We also conducted a chi-square measure of association to determine if there was an association between each of the environmental attitude questions and each knowledge question. We considered a likelihood ratio metric with a p-value of < 0.05 an indication of an association among the responses. If an association was indicated, we considered the lambda value of the analysis; lambda is a measure of 0 -1, with 1 indicating that the independent variable perfectly predicts the dependent variable. We considered a lambda of 0.5 as a strong association between the predictor variable and the question.

References

Boyd, C. S., Davies, K. W., & Collins, G. H. (2017). Impacts of feral horse use on herbaceous riparian vegetation within a sagebrush steppe ecosystem. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 70(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2017.02.001

Bureau of Land Management. (2020). Wild Horse and Burro Program Data. Retrieved from https://www.blm.gov/programs/wild-horse-and-burro/about-the-program/program-data.

Danvir, R. E. (2018). Multiple-use management of western U.S. rangelands: Wild horses, wildlife, and livestock. Human-Wildlife Interactions, 12(1), 5–17.

Irwin, C. W., & Stafford, E. T. (2016). Survey methods for educators: Collaborative survey development (part 1 of 3). Applied Resarch Methods, August.

Kaweck, M. M., Severson, J. P., & Launchbaugh, K. L. (2018). Impacts of wild horses, cattle, and wildlife on riparian areas in Idaho. Rangelands, 40(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rala.2018.03.001

Kellert, S.R. (1984). American attitudes toward and knowledge of animals: An update. In M.W. Fox & L.D. Mickley (Eds.), Advances in animal welfare science 1984/85 (pp. 177-213). Washington, DC: The Humane Society of the United States.

National Research Council. (1980). Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros: Current knowledge and recommended research. National Academy Press, Washington, D. C., USA.

National Research Council. (1982). Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Final Report. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

National Research Council. (2013). Using science to improve the BLM wild horse and burro program: a way forward. National Academy Press, Washington, D. C. USA.

Ostermann-Kelm, S., Atwill, E. R., Rubin, E. S., Jorgensen, M. C., & Boyce, W. M. (2008). Interactions between feral horses and desert bighorn sheep at water. Journal of Mammalogy, 89(2), 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1644/07-mamm-a-075r1.1

Reyes, J. A. L. (2016). Exploring relationships of environmental attitudes, behaviors, and sociodemographic indicators to aspects of discourses: analyses of International Social Survey Programme data in the Philippines. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(6), 1575–1599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9704-4

Scasta, J. D., Beck, J. L., & Angwin, C. J. (2016). Meta-analysis of diet composition and potential conflict of wild horses with livestock and wild ungulates on western rangelands of North America. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 69(4), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2016.01.001

Scasta, J. D., Hennig, J. D., & Beck, J. L. (2018). Framing contemporary U.S. wild horse and burro management processes in a dynamic ecological, sociological, and political environment. Human-Wildlife Interactions 12(1):31-45.

Boyd, C. S., Davies, K. W., & Collins, G. H. (2017). Impacts of feral horse use on herbaceous riparian vegetation within a sagebrush steppe ecosystem. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 70(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2017.02.001

Bureau of Land Management. (2020). Wild Horse and Burro Program Data. Retrieved from https://www.blm.gov/programs/wild-horse-and-burro/about-the-program/program-data.

Danvir, R. E. (2018). Multiple-use management of western U.S. rangelands: Wild horses, wildlife, and livestock. Human-Wildlife Interactions, 12(1), 5–17.

Irwin, C. W., & Stafford, E. T. (2016). Survey methods for educators: Collaborative survey development (part 1 of 3). Applied Resarch Methods, August.

Kaweck, M. M., Severson, J. P., & Launchbaugh, K. L. (2018). Impacts of wild horses, cattle, and wildlife on riparian areas in Idaho. Rangelands, 40(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rala.2018.03.001

Kellert, S.R. (1984). American attitudes toward and knowledge of animals: An update. In M.W. Fox & L.D. Mickley (Eds.), Advances in animal welfare science 1984/85 (pp. 177-213). Washington, DC: The Humane Society of the United States.

National Research Council. (1980). Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros: Current knowledge and recommended research. National Academy Press, Washington, D. C., USA.

National Research Council. (1982). Wild and Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Final Report. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., USA.

National Research Council. (2013). Using science to improve the BLM wild horse and burro program: a way forward. National Academy Press, Washington, D. C. USA.

Ostermann-Kelm, S., Atwill, E. R., Rubin, E. S., Jorgensen, M. C., & Boyce, W. M. (2008). Interactions between feral horses and desert bighorn sheep at water. Journal of Mammalogy, 89(2), 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1644/07-mamm-a-075r1.1

Reyes, J. A. L. (2016). Exploring relationships of environmental attitudes, behaviors, and sociodemographic indicators to aspects of discourses: analyses of International Social Survey Programme data in the Philippines. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(6), 1575–1599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9704-4

Scasta, J. D., Beck, J. L., & Angwin, C. J. (2016). Meta-analysis of diet composition and potential conflict of wild horses with livestock and wild ungulates on western rangelands of North America. Rangeland Ecology and Management, 69(4), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rama.2016.01.001

Scasta, J. D., Hennig, J. D., & Beck, J. L. (2018). Framing contemporary U.S. wild horse and burro management processes in a dynamic ecological, sociological, and political environment. Human-Wildlife Interactions 12(1):31-45.

U. S Public Survey Results (click here)

Survey Team

Jeff Beck, University of Wyoming

Nicki Frey, Utah State University Extension

Jessie Hadfield, Utah State University Extension

Terry Messmer, Utah State University Extension

Mark Nelson, Utah State University Extension

Derek Scasta, University of Wyoming

Loretta Singletary, University of Nevada, Reno Agricultural Experiment Station

Laura Snell, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources

Sam Smallidge, New Mexico State University Extension

Funding provided by University of Nevada, Reno Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University Extension

Nicki Frey, Utah State University Extension

Jessie Hadfield, Utah State University Extension

Terry Messmer, Utah State University Extension

Mark Nelson, Utah State University Extension

Derek Scasta, University of Wyoming

Loretta Singletary, University of Nevada, Reno Agricultural Experiment Station

Laura Snell, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources

Sam Smallidge, New Mexico State University Extension

Funding provided by University of Nevada, Reno Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University Extension