The 'Wild Horse and Burro' Program

Free-roaming horses on lands administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Free-roaming horses on lands administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

In response to public concerns regarding the status and treatment of free-roaming equids (horses and burros), in 1971, Congress passed the Wild Free-Roaming Horse and Burro Act (WHBA). The WHBA gave these animals protection against capture, branding, harrassement or death from any private individual or group. Additionally, the act gave the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service the statutory obligation to manage and protect feral equids in designated herd management areas (HMAs, Public Law 92-195). The intent of the WHBA was to ensure healthy populations of free-roaming equids in ecological balance with other multiple-uses. Other uses include wildlife, livestock, wilderness, and recreation considerations. In 2018, the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service determined a suitable number of free-roaming equids was 26,690 animals on 29.4 million acres in designated HMAs on public land across 10 western states. This number was based on the amount of food (grasses) and water available on public lands. As of 1 March 2019, the Bureau of Land Management estimated that there were 88,090 wild horses and burros inhabiting designated HMAs, surrounding herd areas, and other private and public lands.

To return the free-roaming horse and burro populations to a sustainable level based on 2019 rangeland health, the Bureau of Land Management would have needed to remove more than 65,000 animals from the HMAs.

Tools in the Toolbox

Current management practices that the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service can use to manage horse and burro populations include adoption, immuno-contraception (birth control), and removing animals from the HMAs and holding them in long term facilities. Those animals in long term facilities can then be adopted or sold to private U. S. citizens. While authorized to euthanize free-roaming horses and burros, the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service do not kill animals unless the animals are starving, dehydrated, or injured beyond recovery.

There are currently approximately 50,000 horses held in long-term captive facilities, where they can be adopted, sold, or live out the rest of their lives until they die of natural causes. This costs about $50 million every year to provide for the horses and maintain the holding facilities. Over the past five years, an average of about 2,500 horses have been adopted through the Bureau of Land Management’s adoption services. However, demand to adopt a horse or burro is decreasing while the number of horses needing to be adopted is increasing.

Immuno-contraception (birth control), usually through injections, have been tested and proven effective in reducing population growth rates. Injecting free-roaming horses and burros with contraceptives requires capturing free-roaming horses and burros and directly injecting them with a dose of the birth control. The injections cost about $500 per dose, last about one year, and have variable effectiveness of about 30-70% reduction of birth rate. This method will reduce the number of new horses on rangelands, but doesn't solve the problem of what to do with the over-population of free-roaming horses and burros that live on rangelands right now.

To return the free-roaming horse and burro populations to a sustainable level based on 2019 rangeland health, the Bureau of Land Management would have needed to remove more than 65,000 animals from the HMAs.

Tools in the Toolbox

Current management practices that the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service can use to manage horse and burro populations include adoption, immuno-contraception (birth control), and removing animals from the HMAs and holding them in long term facilities. Those animals in long term facilities can then be adopted or sold to private U. S. citizens. While authorized to euthanize free-roaming horses and burros, the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service do not kill animals unless the animals are starving, dehydrated, or injured beyond recovery.

There are currently approximately 50,000 horses held in long-term captive facilities, where they can be adopted, sold, or live out the rest of their lives until they die of natural causes. This costs about $50 million every year to provide for the horses and maintain the holding facilities. Over the past five years, an average of about 2,500 horses have been adopted through the Bureau of Land Management’s adoption services. However, demand to adopt a horse or burro is decreasing while the number of horses needing to be adopted is increasing.

Immuno-contraception (birth control), usually through injections, have been tested and proven effective in reducing population growth rates. Injecting free-roaming horses and burros with contraceptives requires capturing free-roaming horses and burros and directly injecting them with a dose of the birth control. The injections cost about $500 per dose, last about one year, and have variable effectiveness of about 30-70% reduction of birth rate. This method will reduce the number of new horses on rangelands, but doesn't solve the problem of what to do with the over-population of free-roaming horses and burros that live on rangelands right now.

A young man showing an adopted horse at a competition.

A young man showing an adopted horse at a competition.

The Concern

Without more active management to reduce growth rates on public rangelands the free-roaming horse population could exceed 160,000 by 2025. At this population level, scientists and managers expect more free-roaming horses and burros will die from dehydration and starvation, due to lack of available resources on the landscape. Furthermore, without more active management, the negative impacts of free-roaming horses and burros to native wildlife and rangeland habitat will become irreversible.

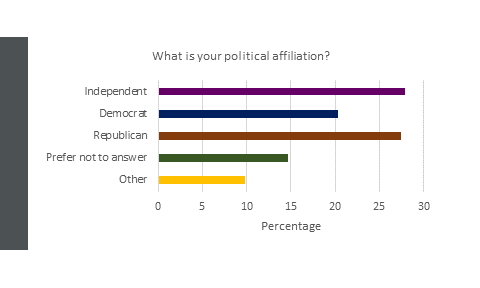

The People

Changing demographics in the United States suggest that public perceptions regarding free-roaming horses and burros management - Wild Horses and Burros on horse management areas - may have changed since the public concern in the 1950-70s that created the WHBA. Shifts in demographics, way of life, and priorities among US citizens suggest that American society today may prefer different management practices than have previously been implemented.

Without more active management to reduce growth rates on public rangelands the free-roaming horse population could exceed 160,000 by 2025. At this population level, scientists and managers expect more free-roaming horses and burros will die from dehydration and starvation, due to lack of available resources on the landscape. Furthermore, without more active management, the negative impacts of free-roaming horses and burros to native wildlife and rangeland habitat will become irreversible.

The People

Changing demographics in the United States suggest that public perceptions regarding free-roaming horses and burros management - Wild Horses and Burros on horse management areas - may have changed since the public concern in the 1950-70s that created the WHBA. Shifts in demographics, way of life, and priorities among US citizens suggest that American society today may prefer different management practices than have previously been implemented.

Surveying the Public to Increase Understanding

Free-roaming horses on lands administered by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service

Free-roaming horses on lands administered by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service

To date, no scientifically rigorous study of U.S. public attitudes regarding the management of free-roaming horses has been completed and published. We began the process of addressing the need to understand the American public's knowledge and opinion of free-roaming horses and burros, by conducting a pilot human dimension study of faculty, staff, and students working and enrolled at Utah State University (USU). The purpose of the study was to provide insights regarding the effect of changing demographics on perceptions about how free-roaming horses and burros may be managed in the future. The lessons we learn from this study will be used to create the next survey, a rigorous national survey of public knowledge and opinions.

Below we report on the basic results of our survey. We asked our respondents more than 40 questions, including some demographic questions. We present some of the basic results of the survey below. As we continue to analyze the data, we will present the results of correlation analyses and modeling influential factors of respondents' opinions. Check back with us to see more data in the near future.

Below we report on the basic results of our survey. We asked our respondents more than 40 questions, including some demographic questions. We present some of the basic results of the survey below. As we continue to analyze the data, we will present the results of correlation analyses and modeling influential factors of respondents' opinions. Check back with us to see more data in the near future.

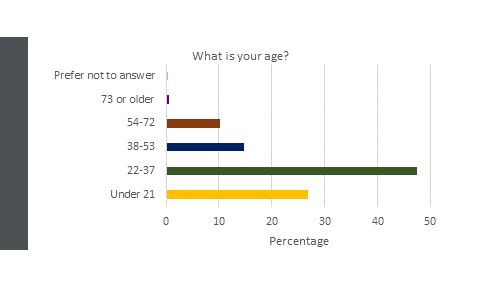

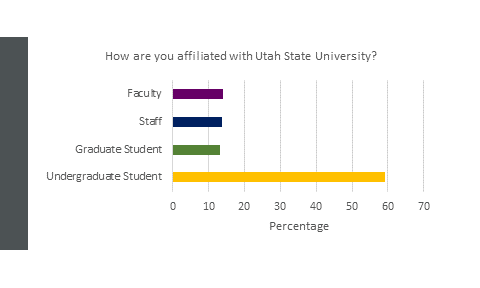

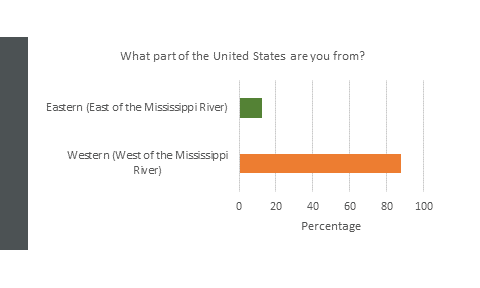

Demographics of our Respondents

The survey was distributed via email with a Qualtrics link attached. A a random sample of 5000 USU student emails (both undergraduate and graduate students) was obtained, as well as a list of all USU faculty and staff emails (approximately 3000 emails). Of the approximate 8000 emails that were sent out, 959 responded, making for a response rate of about 12%. Of these respondents, 72.18% were students, and 27.82% were faculty/staff.

In total, 10 demographic questions were asked. Here we have highlighted four of those demographic questions. Some demographic questions were not included in analysis, due to an overwhelming majority of respondents being the same demographic. For instance, 92% of respondents were Caucasian, and 69% of respondents were Christian, thus race/ethnicity and religious affiliation are not reported here.

In total, 10 demographic questions were asked. Here we have highlighted four of those demographic questions. Some demographic questions were not included in analysis, due to an overwhelming majority of respondents being the same demographic. For instance, 92% of respondents were Caucasian, and 69% of respondents were Christian, thus race/ethnicity and religious affiliation are not reported here.

Knowledge of Free-Roaming Horses and Burros

A total of 20 knowledge-based questions were asked to determine what respondent's already knew about wild horses and burros; 18 of those questions are highlighted below. The two questions not included had a large majority of the same answer. For instance, respondents were asked "Do you think there are wild horse and burro populations in Utah?" Over 86% of respondents selected 'Yes' to this question, so it is not reported here. Likewise, 83% of respondents selected 'No' to the question, "Are you aware of the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934?", so this question is also not reported here.

|

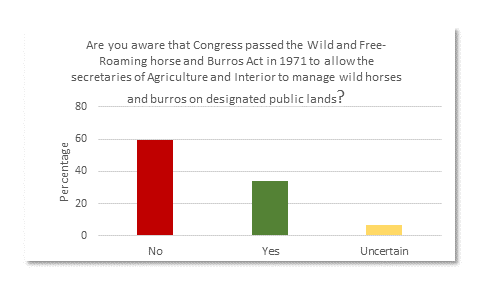

While the correct term is 'free-roaming horses and burros', they are commonly known as 'wild'; to minimize confusion, we used the more common term in our survey. Congress passed the Wild and Free-Roaming Horse and Burros Act in 1971 to allow the secretaries of Agriculture and Interior to manage free-roaming horses and burros on designated public lands. This act provides specific protections to all free-roaming horses and burros on public lands within the United States. Almost 60% of respondents were not aware of this, thus showing the need for greater education to the public about the federal protections wild horse and burros receive. |

|

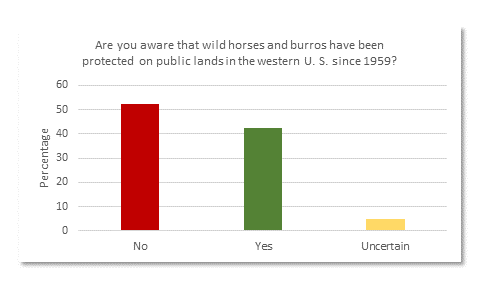

Horses and burros have been protected on public lands in the western U. S. since 1959. This means that free-roaming horses and burros have special federal protection in the United States. Almost 58% of respondents did not know about this, again showing the need for greater education to the public about the federal protections free-roaming horses and burros receive. |

|

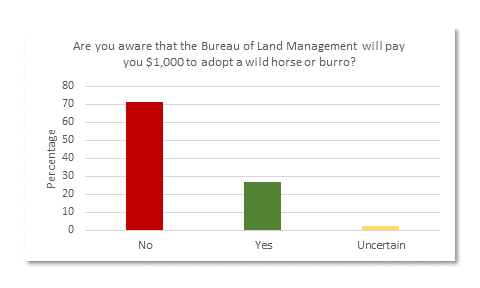

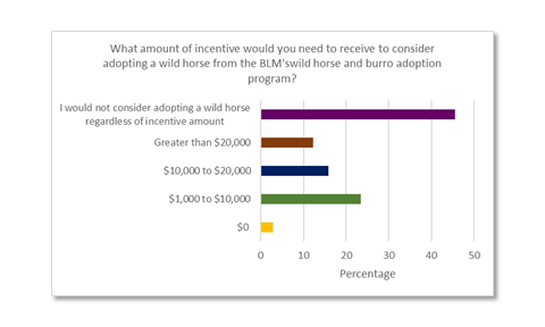

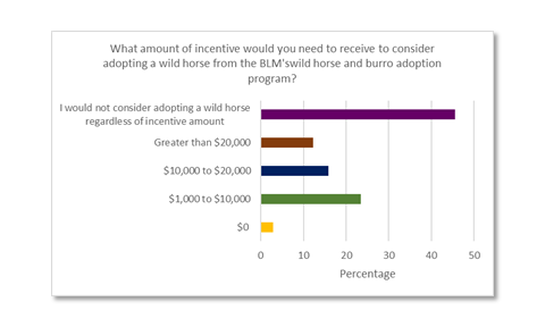

Currently, the Bureau of Land Management will pay a $1,000 incentive to those who adopt a horse from their program. The incentive program is meant to encourage people to adopt a free-roaming horse and provide a good life for the animal. A higher incentive amount may bring down costs associated with the Wild Horse and Burro Program, by reducing the costs needed to hold the animals in long-term care facilities. However, almost 46% of respondents said that they would not consider adopting a horse, regardless of the incentive amount, whereas roughly 28% of respondents said they would consider adopting a horse if the incentive amount was increased from the current amount. This may suggest that adoption alone may not be a enough to decrease the number of horses in long-term care facilities. |

|

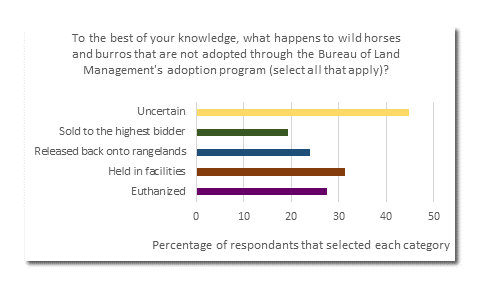

When a horse is not adopted through the Bureau of Land Management’s adoption program, the horse is held in a long term factility, funded by the Bureau of Land Management, until the horse dies of natural causes. Only about 31% of respondents were aware that unadopted wild horses are held in facilities. The remaining 69% were either uncertain or selected the wrong answer. This shows a need for greater education to the public about current wild horse and burro management practices.

|

|

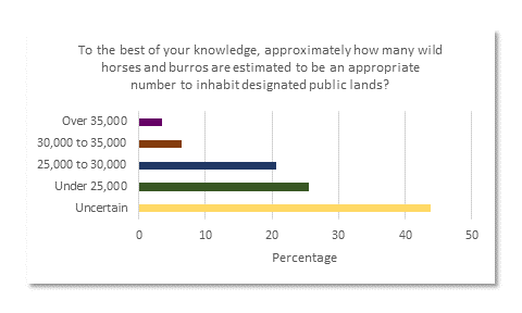

The appropriate management level set by the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service as of March 2018 is 26,690 horses and burros in designated management areas, to ensure both healthy animals and healthy rangelands. About 44% of the respondents were able to correctly identify this number. |

|

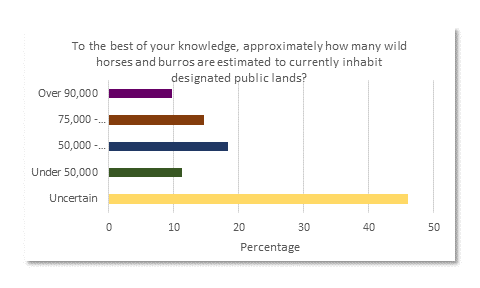

As of March 2019, the Bureau of Land Management estimates that there are approximately 88,090 horses and burros within designated management areas. This is more than three times the suggested number to ensure healthy horses and healthy rangelands. The lack of public knowledge regarding free-roaming horses and burros is demonstrated by the mere 15% of respondents who were able to correctly identify this number. It is notable that almost 10% of the respondents thought that there were more than 90,000 animals! |

|

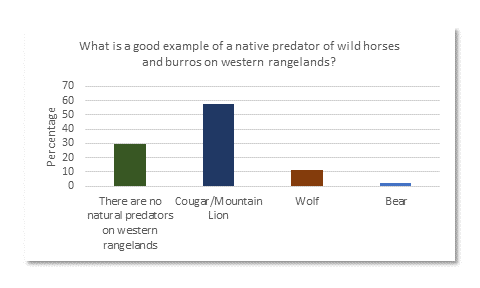

There are no predators of free-roaming horses and burros on western rangelands. There is a misconception that wolves and mountain lions prey on wild horses, however wolves do not inhabit the same regions as free-roaming horses or burros. Infrequently, mountain lion home ranges overlap with free-roaming horses. Because of their size, horses are not an easy prey, and therefore not preferred by mountain lions. Thus, free-roaming horses and burros face no depredation pressure, and their herd numbers are not lessened or managed through natural depredation. |

|

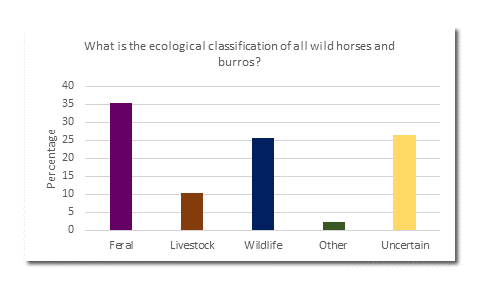

All free-roaming horses and burros in the United States are technically classified as feral; however, the Wild and Free-roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 provided them protection against capture, branding, harassment or death by private individuals or groups. Additionally, those inhabiting federal Horse Management Areas are managed by the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service. The public’s misconception regarding the legal classification of free-roaming horses and burros (only 35% of respondents classified them as feral) may lead to misconception about how these animals are protected. |

|

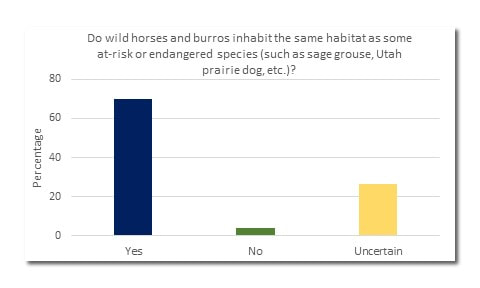

Free-roaming horses and burros inhabit the same habitat as some at-risk or endangered species. Some of these species include sage grouse and Utah prairie dog. Current population numbers of free-roaming horse and burros may negatively impact native wildlife, including these at-risk and endangered species. |

|

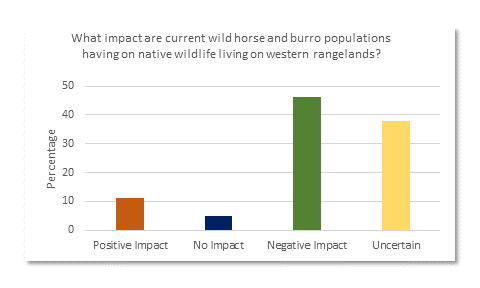

Current free-roaming horse and burro populations are negatively impacting the native wildlife of western rangelands in many areas where they co-occur. The overabundance of free-roaming horses and burros directly compete with native wildlife for food, water, and shelter. Because of their size, they usually out compete any other animal. |

|

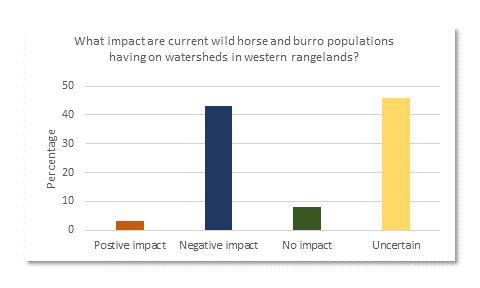

Current free-roaming wild horse and burro populations are negatively impacting watersheds in many western rangelands. Not only do free-roaming horse and burro populations consume more water, but large herds congregate at watering sites, where they exclude or intimidate native wildlife from approaching the water. |

|

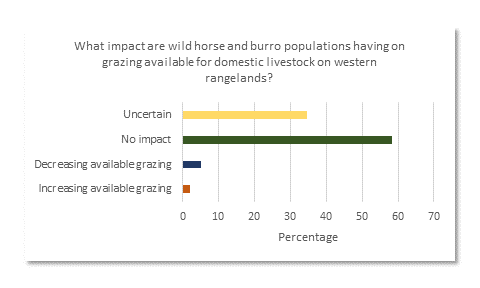

Free-roaming horse and burro populations are decreasing available grazing for domestic livestock on western rangelands in many areas where their populations overlap. Free-roaming horses and burro require more food per body weight, because of their digestion. Because the Bureau of Land Management and U. S. Forest Service cannot manage where horses can go or the time they spend in a field, horses can consume available grasses before cattle or wildlife can access them. Roughly 5% of respondents were able to correctly identify this impact, whereas the majority of respondents were uncertain or thought there was no impact. This shows a need for greater education to the public about current free-roaming horse and burro populations and their impacts.

|

|

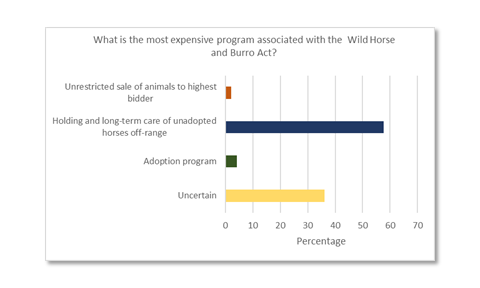

Holding and long-term care of unadopted horses off-range is the most expensive program associated with the Wild Horse and Burro Act. There are currently approximately 46,000 horses held in long-term captive facilities, where horses are meant to live out the rest of their lives until they die of natural causes. The cost per year to taxpayers to maintain horses in these holding facilities is about $50 million. Off-range holding accounted for 58% of total expenditures in 2017.

|

|

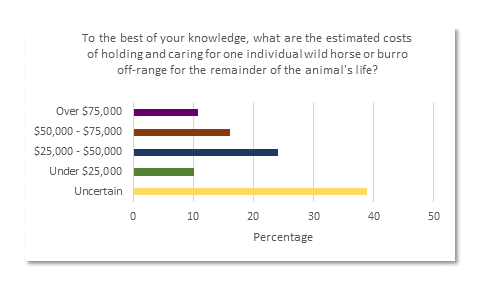

The estimated cost of holding and caring for one individual wild horse or burro off-range for the remainder of the animal's life is approximately $48,000 per animal. There are currently 46,000 horses held in long-term captive facilities. The cost of holding these animals will reach $1.0 billion for just the animals currently being held over their lifetimes.

|

Opinions of Management Options

Respondents were asked to rank their level of support or concern in response to 22 questions about free-roaming horse management. We provided respondents with a small explanation prior to asking the question. You will see the information provided above the set of questions

Information Provided: The appropriate management level set by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and United States Forest Service (USFS) on federally designated lands is set at 26,690 wild horses and burros. As of 1 March 2019, the BLM estimated that there were 88,090 wild horses and burros living on federally designated lands. Over the past five years, an average of about 2,500 horses have been adopted through the BLM’s adoption services. Wild horse and burro population growth rates are about 15% to 20% annually.

|

Most respondents do not think that adoption services alone will be enough to manage current wild horse and burro populations. Similarly, most respondents said that they would not consider adopting a wild horse regardless of the incentive amount. This suggests that even if the incentive amount to adopt a wild horse were to be increased to $20,000, instead of the current $1,000, which could bring down the cost of long-term holding and care for the animals by the BLM, it probably alone will not be enough to help manage population numbers on public rangelands, because most people still would not adopt a wild horse. |

Information Provided: Currently, those who adopt a wild horse or burro through the BLM’s program do not receive full ownership until one year after the adoption date. During the first year after the adoption, the BLM monitors the horse and its conditions and can take the horse back if it is not being properly cared for.

|

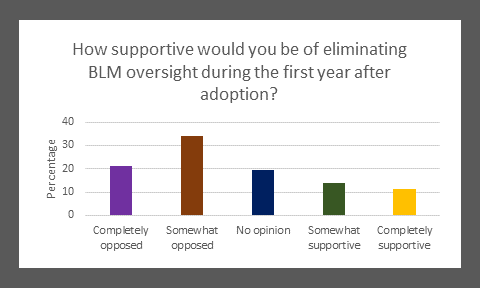

Currently, those who adopt a wild horse or burro through the BLM’s program do not receive full ownership until one year after the adoption date. During the first year after the adoption, the BLM monitors the horse and its conditions and can take the horse back if it is not being properly cared for.

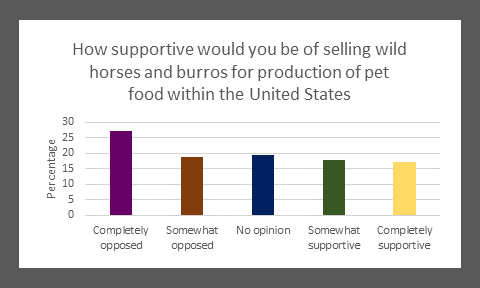

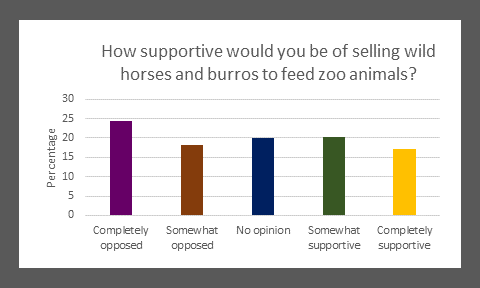

The majority of respondents are opposed to eliminating the year of oversight by the BLM during the first year of adoption. Likewise, the majority of respondents are also opposed to the selling of wild horses and burros for the production of pet food within the United States, as well as selling the meat of wild horses and burros to feed zoo animals. Thus, these management suggestions may not be the best options, as the public will most likely not support them. |

Information Provided: The appropriate management level set by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and United States Forest Service (USFS) on federally designated lands is set at 26,690 wild horses and burros. As of 1 March 2019, the BLM estimated that there were 88,090 wild horses and burros living on federally designated lands.

Over the past five years, an average of about 2,500 horses have been adopted through the BLM’s adoption services. Wild horse and burro population growth rates are about 15% to 20% annually.

Currently, those who adopt a wild horse or burro through the BLM’s program do not receive full ownership until one year after the adoption date. During the first year after the adoption, the BLM monitors the horse and its conditions and can take the horse back if it is not being properly cared for.

Over the past five years, an average of about 2,500 horses have been adopted through the BLM’s adoption services. Wild horse and burro population growth rates are about 15% to 20% annually.

Currently, those who adopt a wild horse or burro through the BLM’s program do not receive full ownership until one year after the adoption date. During the first year after the adoption, the BLM monitors the horse and its conditions and can take the horse back if it is not being properly cared for.

|

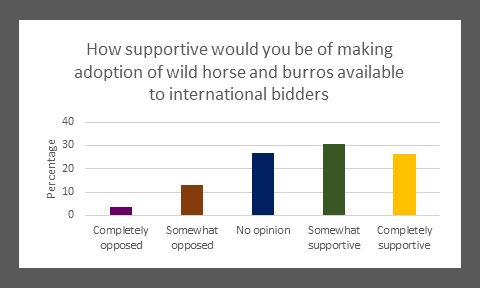

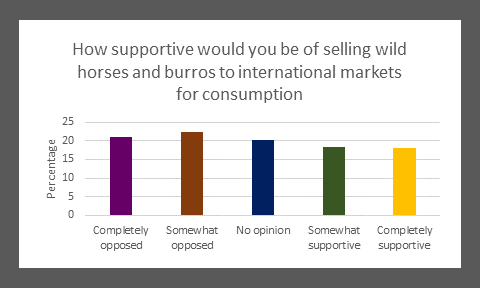

Currently, adoption of a wild horse or burro through the BLM’s adoption program is only available to those within the United States. Although the majority of respondents are supportive of allowing international bidders to adopt a wild horses or burros, they are not supportive or allowing the sell of wild horses and burros to international markets for consumption. Therefore, allowing international bidders to adopt a wild horse or burro may be a good management option, however logistically it may be difficult to enforce the same BLM oversight on foreign lands as it is within the United States. Which could be the difference in whether or not the public approves of the management action since they do not approve of consumption.

|

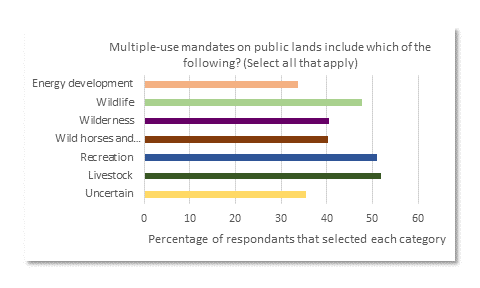

Information Provided: The BLM has the responsibility of deciding how these federally designated lands should be used to fulfill their multiple-use mandate. This includes wild horses and burros, wildlife, livestock, wilderness, and recreation considerations.

|

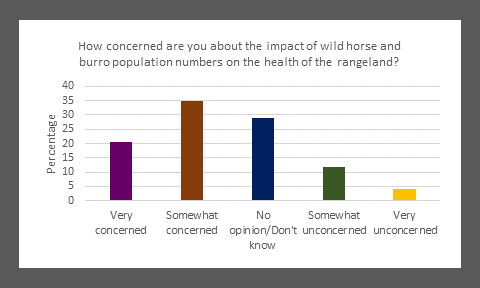

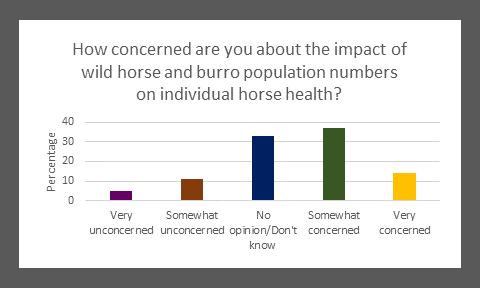

Current population numbers of wild horses and burros on public western rangelands are negatively impacting the health of the rangeland, and many horses die due to starvation, dehydration, or vehicular accidents.

The majority of respondents are concerned about the impact that wild horse and burro populations are having on the rangeland. This suggests that the public may prefer different management actions that can reduce these negative impacts. |

Information Provided: Immunocontraception, predominately PZP-based injections, have been tested and proven effective in reducing growth rates, but not in reducing total number of equids on the rangeland. Injecting wild horses and burros with contraceptives requires multiple captures and injections. PZP costs about $500 per dose, lasts about one year, and has variable effectiveness of approximately 30-70%.

|

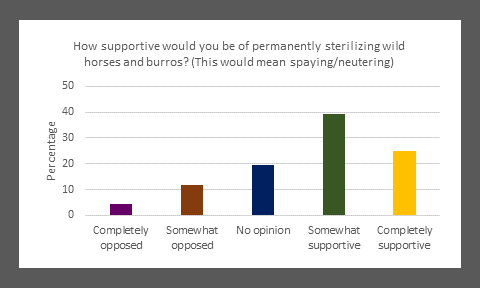

Almost 62% of respondents said that solely no-kill solutions cannot adequately manage populations of wild horses and burros. Likewise, almost 63% of respondents are supportive of permanently sterilizing wild horses and burros. The majority of respondents are also supportive of creating completely non-reproducing herds of wild horses and burros (if possible). This shows that the public is generally supportive of immunocontraception as a management action. However, immunocontraception alone can only decrease the growth rate of herds and does not affect current population numbers. So, it may take several years before the effects of this action can actually be seen. |

Information Provided: Currently, the horses that are not adopted by the BLM’s adoption services are held in long term holding facilities (funded by the BLM with an annual cost of about $50 million) until they die of natural causes. Long term holding of these animals’ costs approximately $40,000 per animal over the animals’ lifetime

|

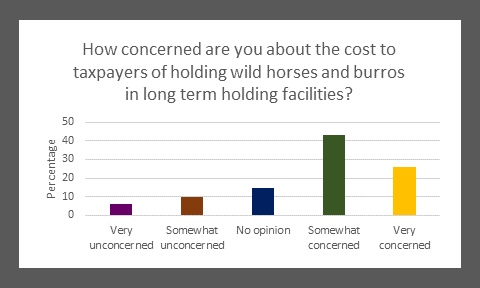

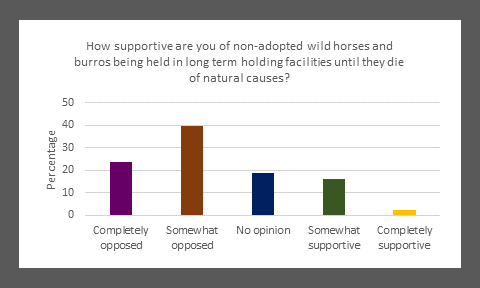

Currently, the horses that are not adopted by the BLM’s adoption services are held in long term holding facilities (funded by the BLM with an annual cost of about $50 million) until they die of natural causes. Long term holding of these animals’ costs approximately $40,000 per animal over the animals’ lifetime. The majority of respondents are opposed to the current practice of holding un-adopted animals in long-term facilities until they die of natural causes. Furthermore, the majority of respondents are concerned about the cost to taxpayers that the holding of these animals causes. This suggests the public may prefer a different management action that what is currently being practiced. Although with just these results alone, it cannot be definitively determined if the public would be more supportive of un-adopted animals being held in long-term facilities until they die of natural causes if the cost to taxpayers were to be reduced (which may or may not realistically be possible)

|

Information Provided: Currently, the horses that are not adopted by the BLM’s adoption services are held in long term holding facilities (funded by the BLM with an annual cost of about $50 million) until they die of natural causes. Long term holding of these animals’ costs approximately $40,000 per animal over the animals’ lifetime.

|

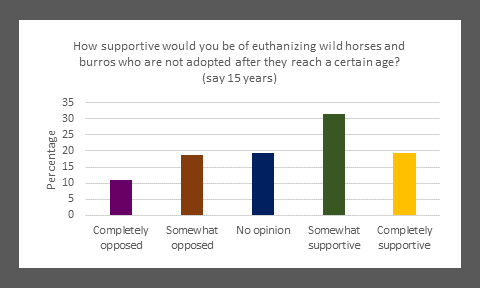

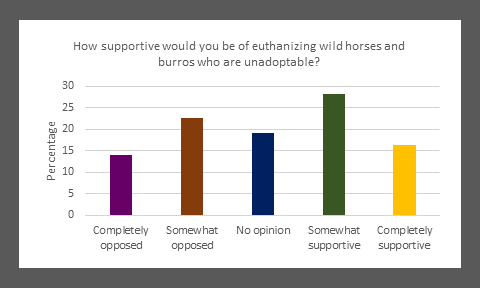

Current laws do not make euthanasia of wild horses and burros illegal, however euthanasia is usually circumvented and rarely happens. A greater proportion of respondents are supportive of euthanasia than are opposed (however it is not a greater than 50% majority, as nearly 20% of respondents selected ‘No Opinion”). However, the majority of respondents are supportive of euthanasia when the animal becomes old. Perhaps further research could be done to determine what age is “old enough” for the majority of respondents to be supportive.

It is interesting to note that although the majority of respondents are in favor of euthanasia, the majority of respondents are opposed to management actions that suggest specific uses for the meat of the animal, such as for pet food or zoo animal meat (as previously mentioned). |

Information Provided: The appropriate management level set by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and United States Forest Service (USFS) on federally designated lands is set at 26,690 wild horse and burros. As of 1 March 2019, the BLM estimated that there were 88,090 wild horse and burros living on federally designated lands.

|

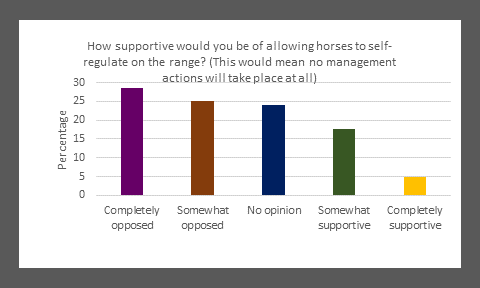

Allowing wild horses and burros to self-regulate on the land would mean that no management actions would take place. Some refer to this as “letting nature take its course.” The majority of respondents are opposed to this no management option.

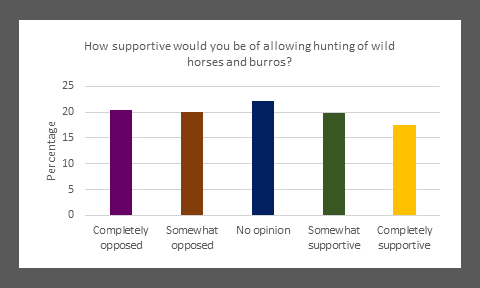

Currently the Bureau of Land Management and United States Forest Service, which are both federal institutions, manage wild horses and burros on public rangelands. Allowing individual states to make up their own laws and regulations for how wild horses and burros are managed within their own state’s boundaries could be a solution used to appease differing public opinions if the public has different opinions in different states. The majority of respondents were supportive of this option. This may be one action that the public can support, however there may be complications or difficulties considering wild populations do not understand or abide by state boundaries. One proposed management action is to establish hunting of wild horses and burros similar to other big game (such as deer or elk). Hunting has been a successful way to manage other wild populations and could be just as effective for wild horses and burros. The respondents were fairly split on whether or not they were supportive or opposed to this option. Allowing hunting could be a useful management tool, and this survey suggests that there will be just as many people supportive of the action as there are opposed to it. |

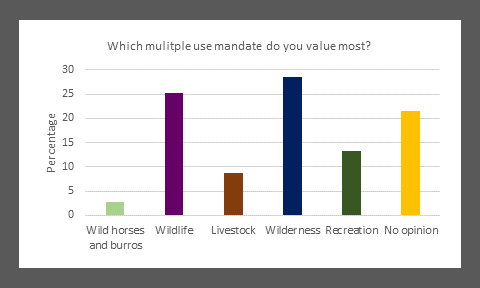

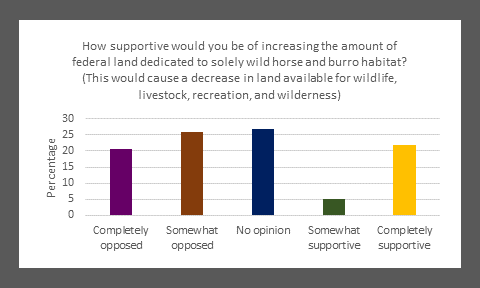

Information Provided: The BLM has the responsibility of deciding how these federally designated lands should be used to fulfill their multiple-use mandate. This includes wild horses and burros, wildlife, livestock, wilderness, and recreation considerations.

|

The multiple-use mandate that a certain respondent values most may lead them to be more or less opposed to certain management actions. Specifically, the suggestion to increase the amount of land available to solely wild horse and burro habitat may be directly related to which mandate is valued most. In general, the two most valued mandates by the entire sample are wilderness and wildlife, with very few people valuing wild horses and burros most. It is not too surprising then, that the majority of people are opposed to increasing the amount of land dedicated to solely wild horses and burros.

|

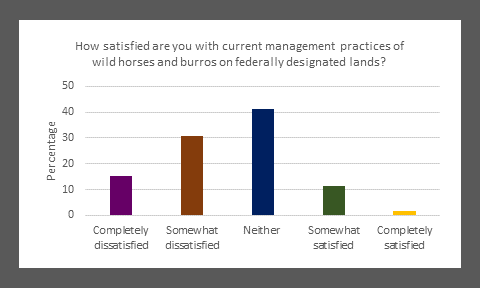

Information Provided: Current management practices of these wild horses and burros includes adoption programs, immunocontraception, and holding of animals in long term facilities.

|

Almost 65% of respondents answered ‘Yes’ when asked if they thought that current management practices of wild horses and burros on federally designated lands needs to change. Nearly 46% of respondents indicated that they were dissatisfied with the current management practices of wild horses and burros on federally designated lands.

Overall, the survey shows that the public would like to see a change in the way that wild horses and burros are managed. While many suggested management actions were primarily opposed by the respondents, there are a few options that the majority of respondents would be in support of. These actions included: making adoption of wild horses and burros available to international bidders (perhaps only if the animal is still cared for and not used for some product, though), sterilization and immunocontraception, and euthanasia. Each of these actions could potentially be implemented and the public would support their implementation. Of course, there are other management options not suggested in this survey that could also be widely effective and supported by the public, but perhaps these results can serve as a starting point for the change in management of wild horses and burros that the public is seeking for |

Our Research Has Been Published

Our website has the most comprehensive explanation of this research project. However, this data has been published in the professional journal, Human Wildlife Interactions. You are welcome to read and download this free publication: digitalcommons.usu.edu/hwi/vol16/iss2/11/