Why Did We Conduct a Survey?

|

|

Managing a federal resource, such as horses, requires the input of US citizens (P.L. 91-190). As one can imagine, the opinions on how to control horse populations differs greatly among regions of the US. In 1982, the National Research Council suggested that control strategies for horse populations must be responsive to public attitudes; a successful program cannot be based solely on biological or economic considerations (National Research Council, 1982). Public views of free-roaming horses range from regarding them as symbols of grace and courage, to that of an invasive species that competes with agriculture and wildlife (Scasta, 2018). In a study of human attitudes toward animals, Kellert (1984) found that horses were the second-most liked animals, behind the domestic dog.

|

The most famous herd in Utah, the Onaqui Mountain herd in Tooele County, is advertised as a popular tourist attraction (wildhorsetourist.com). Meanwhile, horse herds in Millard, Beaver, and Iron County, Utah annually create conflicts for livestock producers and wildlife managers.

Several National Research Council reports (1980, 1982, 2013) highlight the need for research into the social context of horse management, particularly studies that evaluate what aspects of horse management are supported by the public. The information gained from such inquiries could be incorporated into methods to manage horses that also engage public stakeholders. Once decision makers (i.e. public land management agencies, state and local government representatives) understand the different levels of knowledge and opinions of public land management, horses, and horse management options, they can begin to strategically engage a diversity of backgrounds and viewpoints toward creating a management plan that would be supported by most of the public (National Research Council, 2013).

In 2019, the Cooperative Extension System and Agricultural Experiment Stations in Utah and Nevada initiated a Rapid Response Team to focus on free-roaming horse and burro management. This team is made up of specialists from 5 western states that study free-roaming horse biology, ecology, and management, rangeland ecology, and human-wildlife conflict management. The goal of the team is to provide service and momentum to aid the Bureau of Land Management and the US Forest Service in creating a successful free-roaming horse management program for the future. A subcommittee was formed to create a national public survey to gauge the public’s knowledge and opinions of wild horses. Members of the State of Utah, the Bureau of Land Management Wild Horse and Burro Program, and the US Forest Service regional ranger, and scientists involved in studying free-roaming horses reviewed and supported the survey prior to its launch.

In 2019, the Cooperative Extension System and Agricultural Experiment Stations in Utah and Nevada initiated a Rapid Response Team to focus on free-roaming horse and burro management. This team is made up of specialists from 5 western states that study free-roaming horse biology, ecology, and management, rangeland ecology, and human-wildlife conflict management. The goal of the team is to provide service and momentum to aid the Bureau of Land Management and the US Forest Service in creating a successful free-roaming horse management program for the future. A subcommittee was formed to create a national public survey to gauge the public’s knowledge and opinions of wild horses. Members of the State of Utah, the Bureau of Land Management Wild Horse and Burro Program, and the US Forest Service regional ranger, and scientists involved in studying free-roaming horses reviewed and supported the survey prior to its launch.

(Background Information on the Issues of Free-roaming Horses and our Study Methods)

Survey Methods

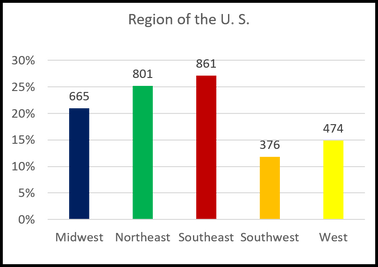

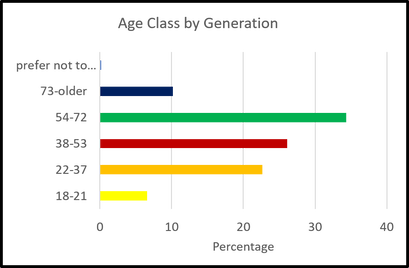

We used a combination of descriptive statistics and chi-square measures of associations for an analysis of the results. Within SPSS (IBM 2020), we used the Crosstabs analysis to conduct the chi-square measures of associations. We analyzed pair-wise association between each question and age, gender, region of the U. S., and income. We also conducted a chi-square measure of association to determine if there was an association between each of the environmental attitude questions and each knowledge question. We considered a likelihood ratio metric with a p-value of < 0.05 an indication of an association among the responses. If an association was indicated, we considered the lambda value of the analysis; lambda is a measure of 0 - 1, with 1 indicating that the independent variable perfectly predicts the dependent variable. We considered a lambda of 0.5 as a strong association between the predictor variable and the question.

Additionally analyses are ongoing and will be reported as they are finished.

Additionally analyses are ongoing and will be reported as they are finished.

Survey Results

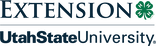

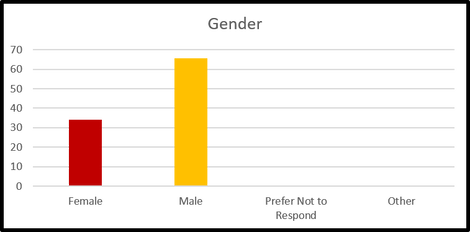

Our goal was to obtain at least 400 responses from each of the 5 regions of the US. We obtained at least this mean in 4 of the 5 regions, in the Southwest we obtained 94% of our goal. We used 3177 responses for our analyses. We measured the influence of each of these demographic questions to each knowledge and opinion question asked in the survey.

U. S. Knowledge of Free-Roaming Horses

Native or Not? Originated or Native?

Horses and burros are not native species of North America; the plants and animals that live in North America have not evolved with them as part of their community. This can be a tricky concept to understand because the Genus Equus originated in North America - so all horses are descendants of the original Equus, although these ancestors looked quite different than horses today. The genus Equus died out in North America 10,000 to 6,000 years ago, although members of this genus continued on in Europe, Asia and Africa and eventually evolved into today's horses, donkeys and zebras.

For at least 6,000 years humans have domesticated horses (Equus ferus caballus) and donkeys (Equus africanus), breeding them for certain characteristics, such as: small and durable donkeys to be used to haul food, Andalusian war horses, light and fast Arabians, and smart Spanish barb horses. This domestication also selected for horses that were easy to train. Through domestication, the association with the wild horse and its ecosystem was disrupted and horses became semi-reliant on humans for food, shelter and water. The only horse species that has never been domesticated or had selective breeding is the Przewalski's horse, that lives in central Asia. It is considered by scientists to be the only truly wild horse species living today.

Horses and burros were introduced to North America in the 1400s with European missionaries and explorers. It is considered an introduction because at this time there were no other Equus ferus caballus in North America. Over time, abandoned and released horses and burros formed herds and by the time European-American settlers began to explore North America in the 1700s, these free-roaming horses and burros had adapted to their habitat and been incorporated into Native American culture. By the mid-1900s, most Americans considered these horses as wild and symbols of freedom and beauty.

In summary, even though Equus originated in North America, any species of this genus died out at some point. The Equus relatives brought to North Americans by Europeans and Asians were not the same animal that had once lived on the continent 10,000 years ago. Thus Equus ferus caballus, the horse as we know it, is non-native to North America. Furthermore, this subspecies has been manipulated by humans for over 6,000 years; this generally means an animal is no longer wild. Any individuals of this species in North America, even if they never have human contact, are ecologically considered feral. The species' long history with humans makes them generally 'tameable', which is how we have a Wild Horse adoption program.

Horses and burros are not native species of North America; the plants and animals that live in North America have not evolved with them as part of their community. This can be a tricky concept to understand because the Genus Equus originated in North America - so all horses are descendants of the original Equus, although these ancestors looked quite different than horses today. The genus Equus died out in North America 10,000 to 6,000 years ago, although members of this genus continued on in Europe, Asia and Africa and eventually evolved into today's horses, donkeys and zebras.

For at least 6,000 years humans have domesticated horses (Equus ferus caballus) and donkeys (Equus africanus), breeding them for certain characteristics, such as: small and durable donkeys to be used to haul food, Andalusian war horses, light and fast Arabians, and smart Spanish barb horses. This domestication also selected for horses that were easy to train. Through domestication, the association with the wild horse and its ecosystem was disrupted and horses became semi-reliant on humans for food, shelter and water. The only horse species that has never been domesticated or had selective breeding is the Przewalski's horse, that lives in central Asia. It is considered by scientists to be the only truly wild horse species living today.

Horses and burros were introduced to North America in the 1400s with European missionaries and explorers. It is considered an introduction because at this time there were no other Equus ferus caballus in North America. Over time, abandoned and released horses and burros formed herds and by the time European-American settlers began to explore North America in the 1700s, these free-roaming horses and burros had adapted to their habitat and been incorporated into Native American culture. By the mid-1900s, most Americans considered these horses as wild and symbols of freedom and beauty.

In summary, even though Equus originated in North America, any species of this genus died out at some point. The Equus relatives brought to North Americans by Europeans and Asians were not the same animal that had once lived on the continent 10,000 years ago. Thus Equus ferus caballus, the horse as we know it, is non-native to North America. Furthermore, this subspecies has been manipulated by humans for over 6,000 years; this generally means an animal is no longer wild. Any individuals of this species in North America, even if they never have human contact, are ecologically considered feral. The species' long history with humans makes them generally 'tameable', which is how we have a Wild Horse adoption program.

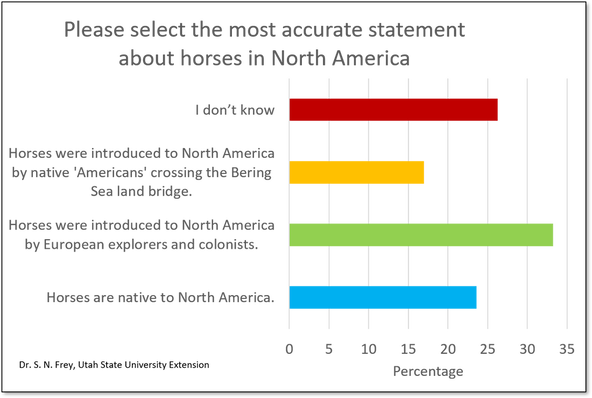

Survey Responses: Most participants did not know that horses (Equus ferus caballus) were introduced to North America by European explorers, missionaries, and colonists. For the US public to understand free roaming horse management, they must understand the natural history of this species.

Wild, Feral, or Free-roaming?

Wild, feral and free-roaming are all scientific terms that are used to refer to horses that are not cared for by a person or a group. Biologically, ‘wild’ refers to a species of animal that has never been domesticated, like elk, deer or pronghorn. Because the horses that we know today have been domesticated for thousands of years, as a species, they are not truly wild. However, some people refer to horses that are descendants from the European explorers as ‘wild’ because they have lived freely on public lands for generations. Perhaps a better term would be 'naturalized'?

The term ‘feral’ refers to an animal that was once domesticated but has since been returned to the wild. For example, a person may own a horse for several years, but for personal reasons decides to release that animal onto public lands (note: this practice is illegal). Horses are not native to North America. All horses that currently live on public lands are descendants of domesticated animals originating in Europe and Asia; thus, they are technically non-native feral animals. Unlike 'wild' animals, most horses can be captured, adopted, and trained to be tame.

Free-roaming means that an animal is not herded or restrained from moving throughout the landscape. When discussing horses, ‘free-roaming’ refers to all horses that live and move freely throughout the land, regardless of their origin, or how long they have lived without human interaction.

Follow this link for more information about why scientists consider horses 'feral'.

Wild, feral and free-roaming are all scientific terms that are used to refer to horses that are not cared for by a person or a group. Biologically, ‘wild’ refers to a species of animal that has never been domesticated, like elk, deer or pronghorn. Because the horses that we know today have been domesticated for thousands of years, as a species, they are not truly wild. However, some people refer to horses that are descendants from the European explorers as ‘wild’ because they have lived freely on public lands for generations. Perhaps a better term would be 'naturalized'?

The term ‘feral’ refers to an animal that was once domesticated but has since been returned to the wild. For example, a person may own a horse for several years, but for personal reasons decides to release that animal onto public lands (note: this practice is illegal). Horses are not native to North America. All horses that currently live on public lands are descendants of domesticated animals originating in Europe and Asia; thus, they are technically non-native feral animals. Unlike 'wild' animals, most horses can be captured, adopted, and trained to be tame.

Free-roaming means that an animal is not herded or restrained from moving throughout the landscape. When discussing horses, ‘free-roaming’ refers to all horses that live and move freely throughout the land, regardless of their origin, or how long they have lived without human interaction.

Follow this link for more information about why scientists consider horses 'feral'.

|

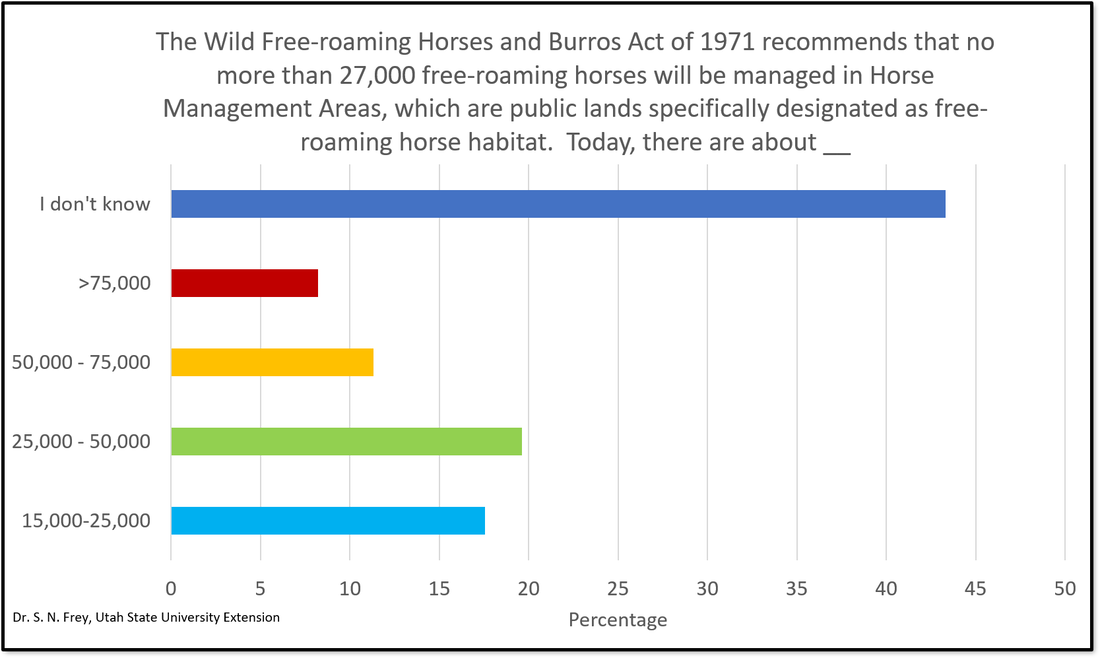

In 1971, Congress passed the Wild Free-roaming Horse and Burro Act to protect free-roaming horses and burros in the western United States from round-ups by private citizens or groups. They determined that free-roaming horses would be managed on public lands designated as Horse Management Areas (HMAs) or Horse Management Territories (HMT), at a population maximum of 26,000 horses. Today, there are approximately > 75,000 ‘wild’ horses living in horse management areas or territories (US Forest Service, 2003; Bureau of Land Management, 2016).

|

Survey Responses: Fewer than 10% of the survey participants knew that there is currently more than 75,000 free roaming horses on public lands. It is possible that the U. S. public's support of management actions for free roaming horses is influenced by how many horses the public thinks exists.

Competition for Food and Water

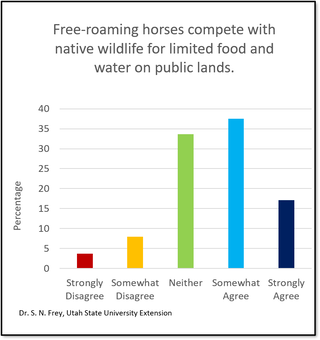

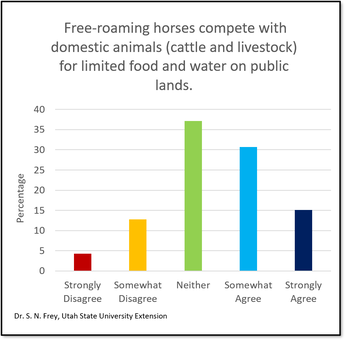

The public lands where free-roaming horses live, including HMAs and HMTs are also commonly referred to as ‘rangelands’. Many of these areas are high-desert shrub and forest ecosystems that have hot, dry summers and cold, snowy winters. Most of the rangeland vegetation in the U. S. consists of grasses, sagebrush, other shrubs, and small trees. Free-roaming horses share this land with native wild ungulates (hooved mammals) including pronghorn (Antilocapra Americana), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), elk (Cervus canadensis), as well as many other mammals, reptiles, and birds. Because free-roaming horses occupy the same habitat as many wildlife species, interactions between free-roaming horses and wildlife are inevitable. Horses are larger than many native wildlife species, so they can be strong competitors for limited resources such as food, water, and shelter. This raises concerns about the ability of horses to out-compete wildlife for food or to change the rangelands to the point that they aren’t suitable for native wildlife species. For a discussion of how these conflicts might happen, please read this short document.

The public lands where free-roaming horses live, including HMAs and HMTs are also commonly referred to as ‘rangelands’. Many of these areas are high-desert shrub and forest ecosystems that have hot, dry summers and cold, snowy winters. Most of the rangeland vegetation in the U. S. consists of grasses, sagebrush, other shrubs, and small trees. Free-roaming horses share this land with native wild ungulates (hooved mammals) including pronghorn (Antilocapra Americana), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), elk (Cervus canadensis), as well as many other mammals, reptiles, and birds. Because free-roaming horses occupy the same habitat as many wildlife species, interactions between free-roaming horses and wildlife are inevitable. Horses are larger than many native wildlife species, so they can be strong competitors for limited resources such as food, water, and shelter. This raises concerns about the ability of horses to out-compete wildlife for food or to change the rangelands to the point that they aren’t suitable for native wildlife species. For a discussion of how these conflicts might happen, please read this short document.

Survey Responses: Most of the survey participants somewhat or strongly agreed that free roaming horses compete with both native wildlife and domestic cattle and livestock for food and water resources on public lands. More than 30% of the respondents had no opinion about the statement, suggesting that they either didn’t care or they didn’t know enough about the topic to have an opinion

Where Do Free-Roaming Horses Live?

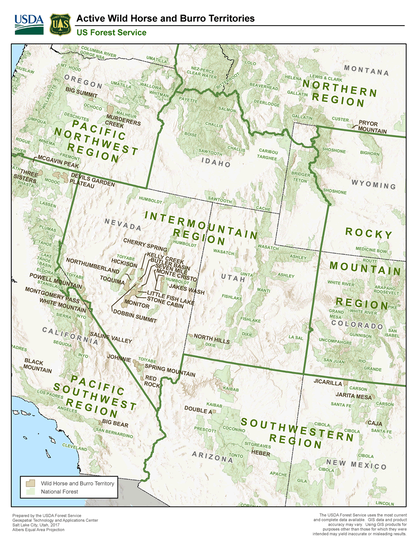

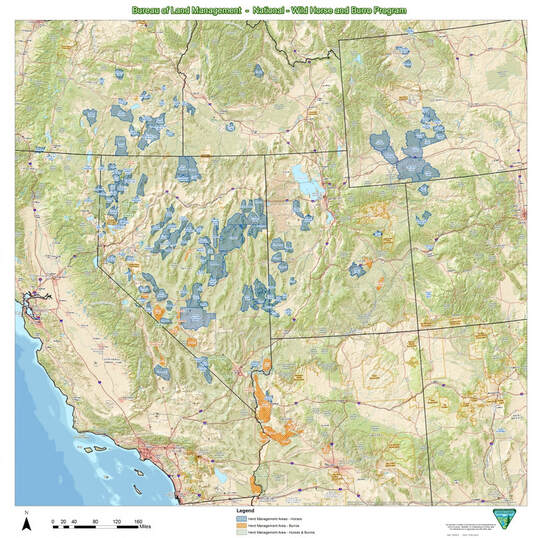

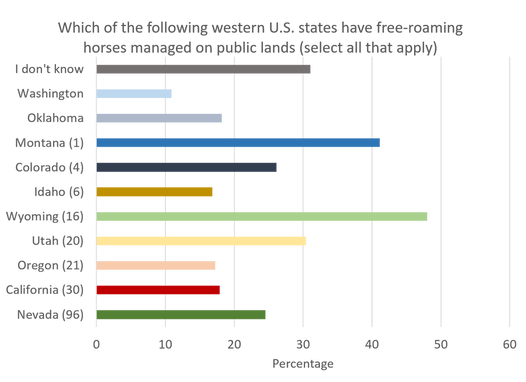

The majority of free-roaming horses are managed in Nevada, California, Oregon, Utah and Wyoming. The Forest Service manages approximately 7,100 wild horses and 900 wild burros on 53 wild horse and burro territories on approximately 2.5 million acres of National Forest System lands in 5 Forest Service regions, 19 national forests, and 9 states. Of these 53 territories, 34 are active and 19 are inactive. Of the 34 active territories, located in Arizona, California, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, and Utah, approximately 24 are jointly managed in cooperation with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) wild horse and burro program. Most of these jointly managed territories are in Nevada. Click the photo of USFS Herd Management Territories to learn more about their program. The BLM manages wild horses and burros in 177 herd management areas across 10 western states. Each HMA is unique in its terrain features, local climate and natural resources, just as each herd is unique in its history, genetic heritage, coloring and size distribution. For example, BLM Nevada manages 83 wild horse and burro herd management areas on approximately 15.6 million acres. The combined appropriate management level for all HMAs in the state is 12,811 animals. Click on the photo of BLM Herd Management Areas to learn more about their program.

|

Survey Responses: The number in parentheses indicates the number of Herd Management Areas or Territories each state has. Many respondents do not know where free-roaming horses live. Due to some influence - movies, Western fiction, social media - many respondents can indicate that Montana and Wyoming have free-roaming horses. Conversely, few indicated that Nevada manages free-roaming horses; this is quite shocking given the number of management areas and territories located in Nevada.

|

|

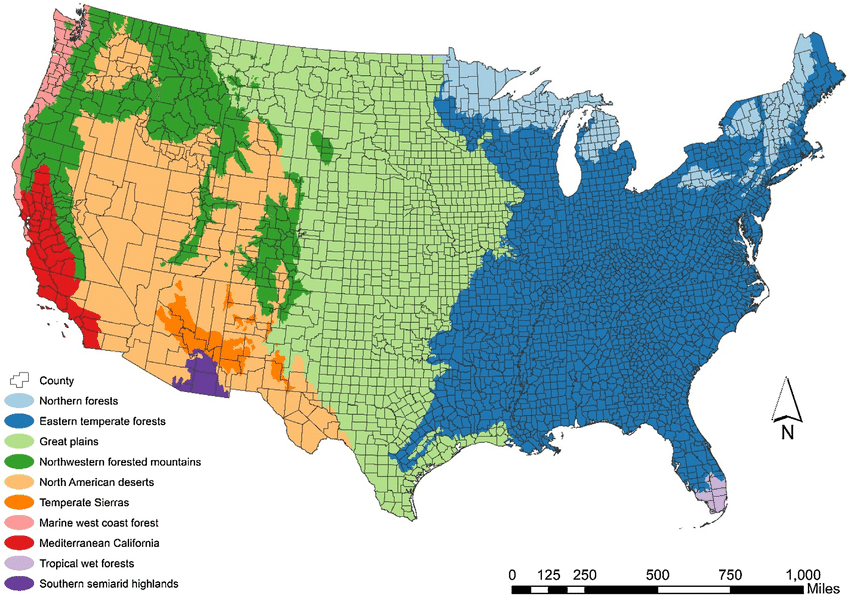

The public lands where free-roaming horses live, including HMAs are commonly called ‘rangelands’. These lands are often high-desert ecosystems that have hot, dry summers and cold, snowy winters such as the North American Deserts and Northwestern Forested Mountains. Most of the rangelands are covered with desert plants, sagebrush and small trees. Free-roaming horses share this land with native wild ungulates including pronghorn (Antilocapra Americana), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), elk (Cervus canadensis), Greater sage-grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus) and many other species.

|

|

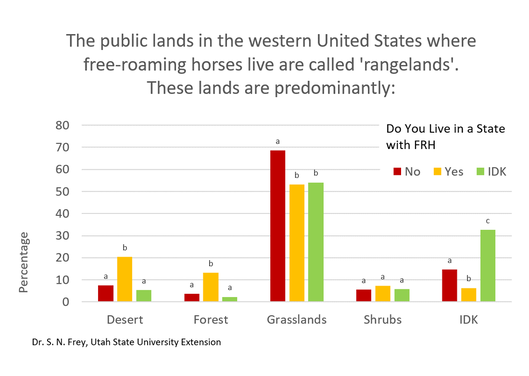

Survey Responses: We asked participants to identify which plant community free roaming horses predominantly live in. Most respondents incorrectly identified Grasslands. While free roaming horses in Wyoming and Montana may exist in grasslands, most free roaming horses live in desert, forest, and shrub ecosystems.

We also asked participants if they lived in a state with free roaming horses, with the hypothesis that those that lived in states with horses would be more likely to correctly identify their habitat. While those that lived in states with horses incorrectly identified grasslands as the predominate habitat, they also indicated deserts and forests more often. |

Managing Free Roaming Horses

What Tools Are Available?

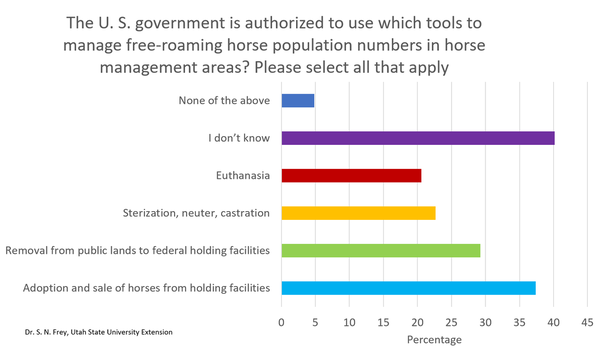

The Wild Free-roaming Horse and Burro Act of 1971 authorized the use of the following methods to control horse herds where they were over the carrying capacity of the land (e. g. there isn't enough food or water to support them).

|

To maintain wild horses and burros in good condition and protect the health of our public lands, the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service must manage the size of horse herd. Currently, there are two common methods to manage free roaming horse populations. First, the Bureau of Land Management and the U. S. Forest Service removes the horses from the public rangelands and places them in long-term holding facilities. Second, these agencies allow the U. S. public to adopt or purchase free roaming horses from these holding facilities. More information about the Bureau of Land Management's program can be found by clicking here. More information about the U. S. Forest Service's program can be found by clicking here.

Survey Responses: Nearly 1/2 the respondents selected "I don't know", which highlights the need for more education and promotion of the Wild Horse and Burro programs. While each of these actions was legal under the original Wild Horse and Burro act, the Wild Horse and Burro program currently relies heavily on removals to federal holding facilities and adoption and sales. Euthanasia is authorized to put down a horse or burro that is sick or dying from starvation or dehydration; this method is not currently used to reduce population numbers because it is currently illegal for the Wild Horse and Burro program to euthanasia healthy horses or burros.

Survey Responses: Nearly 1/2 the respondents selected "I don't know", which highlights the need for more education and promotion of the Wild Horse and Burro programs. While each of these actions was legal under the original Wild Horse and Burro act, the Wild Horse and Burro program currently relies heavily on removals to federal holding facilities and adoption and sales. Euthanasia is authorized to put down a horse or burro that is sick or dying from starvation or dehydration; this method is not currently used to reduce population numbers because it is currently illegal for the Wild Horse and Burro program to euthanasia healthy horses or burros.

Natural Regulation of Horses

|

All hoofed animals within the United States are manged by wildlife managers (e.g. elk, deer, pronghorn), ranchers (e.g. domestic sheep, beef, goats), and range managers (e.g. managing the plants they eat and the water they drink). Elk, deer and pronghorn populations - and other animals considered 'game - are managed at a level appropriate for the forage available through regulating the number of hunting tags. Generally, it is the availability of forage that drives natural population numbers; too many animals and they will die of disease or starvation. Predators will kill a percentage of population each year, although depredation does not usually regulate population numbers.

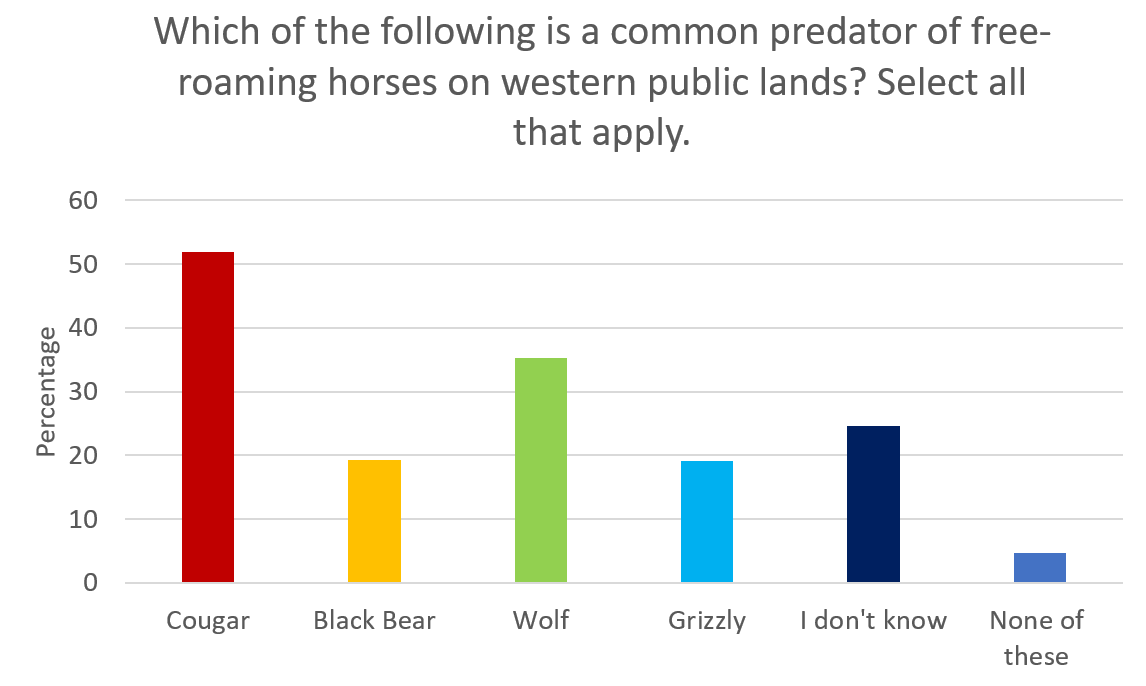

Domestic hoofed animals are managed by regulating the number of animals allowed in grazing allotments each month. Ranchers can dictate how many animals give birth, or slaughter or sell off excess animals to maintain the allowable numbers in their herd. They move their animals from pasture to pasture as dictated by their plans with range managers. Horses and burros are the exceptions. Horses and burros are not managed like wild animals OR domestic animals. Unlike domestic animals, they are not rotated around the landscape at a level that is appropriate for the forage available. Unlike wild hoofed animals, they are not hunted to manage their population numbers. Because they did not evolve with the other plants and animals in North America for the last 10,000 there are no natural predators of free-roaming horses that regularly hunt and kill horses throughout their distribution. |

|

The majority of respondents indicated that cougars (mountain lions, pumas) are common predators of free-roaming horses. In order for cougars to regularly kill horses, as a 'common' predator, cougars and horses must occupy the same land at the same time. Additionally, cougars must learn to see horses as a food source, and learn to successfully kill them without serious injury to themselves. The Great Basin is one region where horses and cougars overlap, and cougars have learned to kill horses (read more here). In other areas where horses occur, this is not a common occurrence. Grizzly bears and wolves often do not live in the same areas as horses, and thus, they rarely kill free-roaming horses. Black bears often do not live in the same areas as free-roaming horses; additionally, they are not large enough to kill adult free-roaming horses.

|

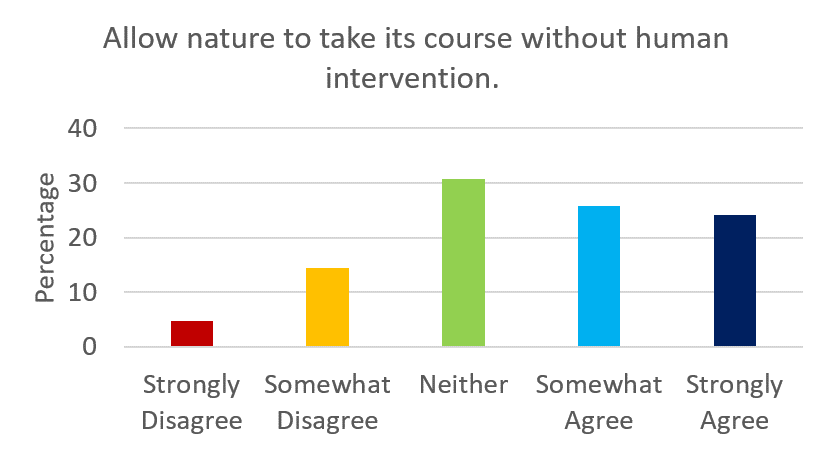

Many people incorrectly think that depredation can and does regulate population numbers of wildlife species; that predators are killing surplus animals and creating an equilibrium in the ecosystem. Perhaps this is why many of our respondents agreed with the idea of letting nature take its course. Unfortunately, predators controlling a population is rarely reality. More often, population numbers are regulated by food availability. Carrying capacity is achieved through starvation, dehydration, disease, and depredation. Starvation and dehydration is the greatest risk for many horse herds. Most range managers do not consider it humane to allow horses to starve to death or die of dehydration. Each years, millions of dollars of taxpayer money is used in emergency round ups to save horses that are in near-death conditions.

Question from the Public: Are there any measures in place or ideas on how to better educate the public regarding free-roaming horses to fill that knowledge gap?

|

There is not a national-level education program in place. However, there are smaller efforts in several states designed to increase public education. For example the University of California's Cooperative Extension program hosts educational competitions for youth, where participants adopt and gentle an adopted free-roaming horse that has been brought off the range. And Utah State University 4-H Extension has created an overnight 'Mustang Camp' where youth can learn about free-roaming horse ecology and then go out and view free-roaming horse herds.

The stumbling point is that usually only people that are already interested in learning about free-roaming horses respond to or look for new information. People tend to look for information that validates their thoughts and opinions. So, how do we increase the knowledge of the public that doesn't know and doesn't really care? People also tend to look for information when they have become angry about an issue or a policy. How can we ensure that they find scientifically credible information that can help them engage in the issue and make informed decisions? We don't know. But we are working on it. |

The quick answer is 'Yes, there are'. However, the coordination is very complicated. Usually, each state in the U.S. has direct management of the wildlife in their state, while the federal agencies such as the US Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, National Wildlife Refuge, etc. manage the land. Such is the case for elk, deer, and all other hooved animals. Because horses located within herd management areas and herd management territories are listed under federal management, the states no longer have direct control over the populations of these animals. However, they are in direct coordination with the US Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management because they are trying to balance horse populations with the wildlife populations that the states do have direct management of.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the US Forest Service (USFS) collaborate with various states in multiple ways to manage wild horse populations effectively. These collaborations include joint management programs, resource sharing, and community engagement initiatives. Some notable collaborations between the BLM, the USFS and states include:

By working together, agencies aim to manage wild horse populations sustainably while balancing the needs of wildlife, livestock, and other public land users

Coordination between federal and tribal agencies also occurs. Each tribe has its own relationship with free-roaming horses, and federal agencies consider these relationships when managing horses on federal lands near tribal lands. Several Native American tribes in North America actively manage wild or free-roaming horses, often as part of their cultural heritage and land management practices. Some of these tribes include:

Additionally, several Native American tribes manage wild horses in off-range facilities, often in collaboration with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or other agencies. These off-range facilities can include long-term pastures and holding facilities where horses are cared for after being removed from the range. Some of the tribes involved in managing off-range facilities include:

These tribes play a crucial role in the management and care of wild horses, ensuring their well-being while balancing ecological and cultural considerations.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the US Forest Service (USFS) collaborate with various states in multiple ways to manage wild horse populations effectively. These collaborations include joint management programs, resource sharing, and community engagement initiatives. Some notable collaborations between the BLM, the USFS and states include:

- Adoption and Sales Programs: The BLM and the USFS often partner with state agencies to promote wild horse adoption and sales programs. These programs aim to find homes for excess horses, reducing the number of animals on the range and in holding facilities.

- Joint Roundups and Gathers: The BLM and the USFS collaborate with state wildlife and agricultural agencies to conduct roundups and gathers of wild horses. These operations help manage populations to maintain ecological balance on public lands.

- Off-Range Pastures and Holding Facilities: The BLM and the USFS work with states to identify and manage off-range pastures and holding facilities. These facilities provide long-term care for horses that cannot be adopted or sold.

- Fertility Control Programs: Collaborative efforts between the BLM, the USFS, and states often include fertility control initiatives. These programs aim to manage herd growth through methods such as the administration of contraceptive vaccines.

- Habitat Improvement Projects: The BLM, the USFS, and state agencies work together on habitat improvement projects to ensure that wild horse populations have access to sustainable rangelands. These projects may include water source development, vegetation management, and infrastructure improvements.

- Research and Monitoring: The BLM and the USFS collaborate with state wildlife and natural resource agencies to conduct research and monitoring of wild horse populations. This data helps inform management decisions and ensures the health of the herds and the ecosystems they inhabit.

- Public Education and Outreach: The BLM, the USFS, and states often engage in joint public education and outreach efforts to raise awareness about wild horse management issues. These initiatives help build community support and involvement in wild horse programs.

- Emergency Response and Coordination: During emergencies such as droughts, wildfires, or severe winters, the BLM, USFS, and state agencies coordinate response efforts to ensure the safety and well-being of wild horses.

By working together, agencies aim to manage wild horse populations sustainably while balancing the needs of wildlife, livestock, and other public land users

Coordination between federal and tribal agencies also occurs. Each tribe has its own relationship with free-roaming horses, and federal agencies consider these relationships when managing horses on federal lands near tribal lands. Several Native American tribes in North America actively manage wild or free-roaming horses, often as part of their cultural heritage and land management practices. Some of these tribes include:

- The Navajo Nation: Located in the southwestern United States, the Navajo Nation has a significant population of free-roaming horses, which they manage through roundups and adoption programs.

- The Yakama Nation: Located in Washington State, the Yakama Nation actively manages a population of wild horses on their reservation, employing roundups and adoption initiatives.

- The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes: These tribes in Idaho manage wild horses on their Fort Hall Reservation through various herd management practices.

- The Warm Springs Tribes: In Oregon, the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs manage free-roaming horse populations on their reservation.

- The Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes: Located in Nevada and Oregon, these tribes manage wild horses on their lands through roundups and other management practices.

- The Ute Indian Tribe: In Utah, the Ute Tribe actively manages wild horse populations on their reservation through controlled roundups and adoption programs.

Additionally, several Native American tribes manage wild horses in off-range facilities, often in collaboration with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or other agencies. These off-range facilities can include long-term pastures and holding facilities where horses are cared for after being removed from the range. Some of the tribes involved in managing off-range facilities include:

- The Navajo Nation: The Navajo Nation manages off-range facilities where wild horses are kept after being rounded up. These facilities are used for holding and adoption purposes.

- The Northern Arapaho Tribe: Located in Wyoming, the Northern Arapaho Tribe manages off-range facilities for wild horses. They work with the BLM to provide long-term care for these animals.

- The Northern Cheyenne Tribe: In Montana, the Northern Cheyenne Tribe manages off-range facilities where they care for wild horses removed from the range.

- The Fort McDermitt Paiute and Shoshone Tribes: These tribes manage off-range facilities in Nevada and Oregon, providing care and management for wild horses in partnership with federal agencies.

- The Yakama Nation: The Yakama Nation also manages off-range facilities for wild horses, focusing on population control and humane treatment.

- The Pine Ridge Oglala Sioux Tribe: In South Dakota, the Pine Ridge Oglala Sioux Tribe manages off-range facilities for wild horses, providing a safe environment for these animals.

These tribes play a crucial role in the management and care of wild horses, ensuring their well-being while balancing ecological and cultural considerations.

Much of the information that we have regarding the climate trends for the Intermountain West - where most free-roaming horses are located - looks grim for the animals living on rangelands. This region characterized by its arid and semi-arid climate, diverse ecosystems, and dependence on water resources. Some of the key projected impacts include:

- Increased Temperatures: The Intermountain West is expected to experience rising average temperatures, with more frequent and intense heatwaves. This warming trend will affect ecosystems, water resources, and human health.

- Altered Precipitation Patterns: Climate change is likely to lead to changes in precipitation patterns, including more intense but less frequent rainfall events. This could result in longer periods of drought interspersed with heavy storms, affecting water availability and increasing the risk of flooding.

- Reduced Snowpack: Higher temperatures are projected to reduce snowpack in the mountains, which is a crucial source of water for the region. Reduced snowpack will lead to lower streamflows in the spring and summer, impacting water supplies for rangeland ecosystems.

- Increased Wildfire Risk: Warmer temperatures, prolonged droughts, and changing precipitation patterns are expected to increase the frequency and intensity of wildfires in the Intermountain West. This will have significant impacts on forests, air quality, and human and wildlife communities.

- Changes in Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Climate change will alter habitats and affect species distributions. Some species may be unable to adapt quickly enough to changing conditions, leading to shifts in biodiversity and ecosystem dynamics. This can impact agriculture, wildlife management, and conservation efforts.

|

|

Please enjoy this presentation of the study. We presented our results to the FREES Wild Horse and Burro Summit in Cody, Wyoming in October 2020. |

|

|

Please enjoy this presentation of our study, presented to the Utah State University Stock and Flock Talks in January 2021. This presentation discusses additional data specifically on Public Knowledge.

|

Our Research Is Currently Being Published in Professional Journals

If this website has been interesting to you, we welcome you to download our publications on the subject.

New Research in Wild Horse Management. 2022. Human-Wildlife Interactions Journal Volume 16, Issue 2.

Public Knowledge of Free-Roaming Horses in the United States (escholarship.org). 2022. in the Proceedings of the 30th Vertebrate Pest Conference.

Western US Residents’ Knowledge of Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Their Management on Federal Public Lands. 2024. Rangeland Ecology and Management

Survey Team:

Jeff Beck, University of Wyoming

Nicki Frey, Utah State University Extension

Jessie Hadfield, Utah State University Extension

Terry Messmer, Utah State University Extension

Mark Nelson, Utah State University Extension

Derek Scasta, University of Wyoming

Loretta Singletary, University of Nevada, Reno Agricultural Experiment Station

Laura Snell, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources

Sam Smallidge, New Mexico State University Extension

Funding provided by University of Nevada, Reno Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University Extension

Nicki Frey, Utah State University Extension

Jessie Hadfield, Utah State University Extension

Terry Messmer, Utah State University Extension

Mark Nelson, Utah State University Extension

Derek Scasta, University of Wyoming

Loretta Singletary, University of Nevada, Reno Agricultural Experiment Station

Laura Snell, University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources

Sam Smallidge, New Mexico State University Extension

Funding provided by University of Nevada, Reno Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University Agricultural Experiment Station, Utah State University Extension