Gila Monster

By Laura Allard and Dr. Frey

Biology and Identification

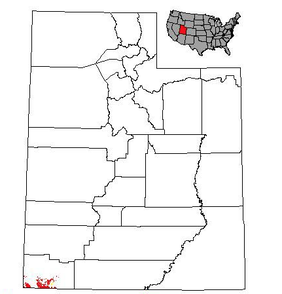

The gila monster (pronounced ‘Hee-la’), Heloderma suspectum, is a slow-moving species of venomous lizard found within Utah, specifically in the Southwestern corner of Washington County, near where Utah meets both Arizona and Nevada. This is the northern extent of their distribution, which stretches from Sinaloa, Mexico to Washington County, Utah and from SW New Mexico to the Colorado River. The best place to find them in Utah is in the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve in Washington County.

Gila monsters are easily identified by their black and orange/yellow, beaded skin. They can be mistaken with the closely-related Mexican beaded lizard (Heloderma horridum) who is both larger and duller in coloration than the gila monster. The gila blends well into the ‘red rocks’ of southern Utah, with its irregular pattern of black and pinkish-orange stripes and spots. Gila monsters are considered dietary generalist, eating eggs and nestlings of ground nesting vertebrates, and sometimes even scavenging. Three or 4 large meals can equate to a gila monster’s yearly energy needs (Gienger et al. 2013). Gila monsters are solitary creatures, living in burrows or shadowy cracks in rocks, close to the location of potential food. For example, during the bird nesting season, gila monsters will be found close to ground nesting bird habitat.

Gila monsters may live up to 20 years in the wild, growing up to 13 inches in length (Smith et al., 2010), although some have been known to be as long as 22 inches. Because of their venomous bite, they are fairly safe from predators. They are not sexually mature until they are 3-5 years old. Mating begins in late April in most areas, after which the female will lay anywhere from 2 to 30 eggs. These will incubate for up to 10 months -- during this time they are at risk from being eaten by coyotes, badgers, and even the female gila monsters, if other food is scarce. Hatchlings are seen the following April. (Goldberg & Lowe, 1997).

By Laura Allard and Dr. Frey

Biology and Identification

The gila monster (pronounced ‘Hee-la’), Heloderma suspectum, is a slow-moving species of venomous lizard found within Utah, specifically in the Southwestern corner of Washington County, near where Utah meets both Arizona and Nevada. This is the northern extent of their distribution, which stretches from Sinaloa, Mexico to Washington County, Utah and from SW New Mexico to the Colorado River. The best place to find them in Utah is in the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve in Washington County.

Gila monsters are easily identified by their black and orange/yellow, beaded skin. They can be mistaken with the closely-related Mexican beaded lizard (Heloderma horridum) who is both larger and duller in coloration than the gila monster. The gila blends well into the ‘red rocks’ of southern Utah, with its irregular pattern of black and pinkish-orange stripes and spots. Gila monsters are considered dietary generalist, eating eggs and nestlings of ground nesting vertebrates, and sometimes even scavenging. Three or 4 large meals can equate to a gila monster’s yearly energy needs (Gienger et al. 2013). Gila monsters are solitary creatures, living in burrows or shadowy cracks in rocks, close to the location of potential food. For example, during the bird nesting season, gila monsters will be found close to ground nesting bird habitat.

Gila monsters may live up to 20 years in the wild, growing up to 13 inches in length (Smith et al., 2010), although some have been known to be as long as 22 inches. Because of their venomous bite, they are fairly safe from predators. They are not sexually mature until they are 3-5 years old. Mating begins in late April in most areas, after which the female will lay anywhere from 2 to 30 eggs. These will incubate for up to 10 months -- during this time they are at risk from being eaten by coyotes, badgers, and even the female gila monsters, if other food is scarce. Hatchlings are seen the following April. (Goldberg & Lowe, 1997).

An Historic Misnomer

The gila monster both protects itself and aids itself in feeding via its venom, that is produced from glands within the lower jaw (mandible). Ducts from the lower jaw lead to grooved teeth; these cause the venom to be injected into food as the lizard chews. In contrast, snakes forcibly eject their venom from their top two incisors (eye-teeth). The venom of a gila monster is a cocktail of 6 poisons, each helping to incapacitate its victim. The gila monster’s venom is as toxic as a Great Basin Rattlesnake, however only a relatively small amount of venom is released when it bites. A gila monster’s bite hasnot directly killed a single person; most deaths are related to improper care of the bite location.

History with Humans

Humans have reportedly created many negative stories surrounding the Gila Monster, hence the latter part of its name: “Monster”. Early English-American Pioneers apparently had many run-ins with these lizards, creating myths that the lizard had “toxic breath” and that a bite from the lizard would certainly end in death.

Later examination of the Gila Monster’s venom would show that it is a neurotoxin with the same capabilities that of the Coral Snake, but that the Gila Monster releases much less quanitity of said venom compared to the Coral Snake. Regardless of its toxicity however, the Gila Monster’s bite has not killed a single person since 1939, with many of the deaths prior to that date speculated to have been due to improper care of the venom injection.

In the Old West, it was common belief that treatment of the bite, or injection site, of a venomous creature would solve the problem of the victim. Since those times, it has been known that “sucking out the venom” from a bite wound is both impractical and ineffective, because the venom will enter the bloodstream and begin circulating immediately after a bite occurs.

Species Management

Considering the slow, easily anticipated movements of this lizard, the gila monster poses little threat to healthy humans. Unfortunately, the negative reputation created by early pioneers and spread through oral tradition, has caused people to be needlessly afraid of gila monsters.

Most visitors of the desert will never see a gila monster, because they hide in the shade during the heat of the day. In fact, gila monsters spend most of their lives in burrows and crevices (Gienger et al, 2013). However should you be lucky enough to see a gila monster, do not try to handle the lizard. A defensive lizard will let you know it is nearby by hissing. Leave the lizard where it is and slowly walk away from the area. Handling the lizard will most likely result in getting bitten. A gila monster envenomates a human by biting and not letting go, allowing the venom to penetrate through the open wound. Envenomations by gila monsters may exhibit a range of symptoms including: including extreme pain, swelling around the bite, nausea, fever, faintness, heart attack, irregular heartbeat, low blood pressure, and the inability of blood to clot (Koludarov et al. 2014).

If you get bitten by a gila monster, DON’T PANIC. A gila monster bite will not cause immediate mortal peril.

References

Beck, D. D., Martin B. E., Lowe C. H., & Wiewandt T., Greene H. (2005). Biology of Gila Monsters and Beaded Lizards. University of California Press.

Gienger, C. M., Tracey, C. R., & Zimmerman, L. C. (2013). Thermal responses to feeding in a secretive and specialized predator (Gila monster, Heloderma suspectum). Journal of Thermal Biology, 38, 143-147.

Goldberg, S. R., and Lowe, C. H. (1997). Reproductive cycle of the gila monster, Heloderma suspectum, in Southern Arizona. Journal of Herpetology, 31, 161-166.

Koludarov, I., Jackson, T. N. W., Sunagar, K., Nouwens, A., Hendrikx, I. & Fry, B. G. (2014). Fossilized Venom: The Unusually Conserved Venom Profiles of Heloderma Species (Beaded Lizards and Gila Monsters). Toxins (Basel)6(12): 3582–3595.

Poisindex ® Toxologic Managements. (1984). Gila Monster (Heloderma suspectum). Accessed September 2018 at http://herpetology.com/helobite.txt

Smith, J. J., Amarello, M., & Goode, M. (2010). Seasonal growth of free-ranging gila monsters (Heloderma suspectum) in a Southern Arizona population. Journal of Herpetology, 44, 484-488.

The gila monster both protects itself and aids itself in feeding via its venom, that is produced from glands within the lower jaw (mandible). Ducts from the lower jaw lead to grooved teeth; these cause the venom to be injected into food as the lizard chews. In contrast, snakes forcibly eject their venom from their top two incisors (eye-teeth). The venom of a gila monster is a cocktail of 6 poisons, each helping to incapacitate its victim. The gila monster’s venom is as toxic as a Great Basin Rattlesnake, however only a relatively small amount of venom is released when it bites. A gila monster’s bite hasnot directly killed a single person; most deaths are related to improper care of the bite location.

History with Humans

Humans have reportedly created many negative stories surrounding the Gila Monster, hence the latter part of its name: “Monster”. Early English-American Pioneers apparently had many run-ins with these lizards, creating myths that the lizard had “toxic breath” and that a bite from the lizard would certainly end in death.

Later examination of the Gila Monster’s venom would show that it is a neurotoxin with the same capabilities that of the Coral Snake, but that the Gila Monster releases much less quanitity of said venom compared to the Coral Snake. Regardless of its toxicity however, the Gila Monster’s bite has not killed a single person since 1939, with many of the deaths prior to that date speculated to have been due to improper care of the venom injection.

In the Old West, it was common belief that treatment of the bite, or injection site, of a venomous creature would solve the problem of the victim. Since those times, it has been known that “sucking out the venom” from a bite wound is both impractical and ineffective, because the venom will enter the bloodstream and begin circulating immediately after a bite occurs.

Species Management

Considering the slow, easily anticipated movements of this lizard, the gila monster poses little threat to healthy humans. Unfortunately, the negative reputation created by early pioneers and spread through oral tradition, has caused people to be needlessly afraid of gila monsters.

Most visitors of the desert will never see a gila monster, because they hide in the shade during the heat of the day. In fact, gila monsters spend most of their lives in burrows and crevices (Gienger et al, 2013). However should you be lucky enough to see a gila monster, do not try to handle the lizard. A defensive lizard will let you know it is nearby by hissing. Leave the lizard where it is and slowly walk away from the area. Handling the lizard will most likely result in getting bitten. A gila monster envenomates a human by biting and not letting go, allowing the venom to penetrate through the open wound. Envenomations by gila monsters may exhibit a range of symptoms including: including extreme pain, swelling around the bite, nausea, fever, faintness, heart attack, irregular heartbeat, low blood pressure, and the inability of blood to clot (Koludarov et al. 2014).

If you get bitten by a gila monster, DON’T PANIC. A gila monster bite will not cause immediate mortal peril.

- DO Immediately apply compression to the bite site

- DO pay attention to the bite - not all bites inject venom. A non-venomous bite won’t hurt more than what one might expect from being bitten by an animal. ○ A venomous bite will become increasingly painful within 15 minutes of being bitten.

- DO Seek immediate medical attention.

- DO NOT wait for symptoms to appear. Seek immediate medical attention.

- DO NOT attempt to suck the poison out with your mouth or other instrument

- DO NOT attempt to detach the gila monster from the body part. You may break off its teeth, leaving them embedded in the wound, which can introduce bacteria and cause complications to neutralizing the venom.

References

Beck, D. D., Martin B. E., Lowe C. H., & Wiewandt T., Greene H. (2005). Biology of Gila Monsters and Beaded Lizards. University of California Press.

Gienger, C. M., Tracey, C. R., & Zimmerman, L. C. (2013). Thermal responses to feeding in a secretive and specialized predator (Gila monster, Heloderma suspectum). Journal of Thermal Biology, 38, 143-147.

Goldberg, S. R., and Lowe, C. H. (1997). Reproductive cycle of the gila monster, Heloderma suspectum, in Southern Arizona. Journal of Herpetology, 31, 161-166.

Koludarov, I., Jackson, T. N. W., Sunagar, K., Nouwens, A., Hendrikx, I. & Fry, B. G. (2014). Fossilized Venom: The Unusually Conserved Venom Profiles of Heloderma Species (Beaded Lizards and Gila Monsters). Toxins (Basel)6(12): 3582–3595.

Poisindex ® Toxologic Managements. (1984). Gila Monster (Heloderma suspectum). Accessed September 2018 at http://herpetology.com/helobite.txt

Smith, J. J., Amarello, M., & Goode, M. (2010). Seasonal growth of free-ranging gila monsters (Heloderma suspectum) in a Southern Arizona population. Journal of Herpetology, 44, 484-488.