Stray Cats

Featured Animal: September 2015

By Dr. Nicki Frey

Stray Cats in Your Neighborhood

Each fall thousands of stray and feral cats begin to look for safe, warm homes for the winter; it is during this time that homeowners begin to see them around their homes more often. Not only can the outdoors be a harsh environment for a cat, cats can be detrimental to the environment. What to do with stray and feral cats in our towns is a divisive subject with some folks wanting to protect and sustain them with others supporting euthanasia (humane death). Because stray and feral cats are domesticated animals, their future is directly our responsibility.

House, stray and feral cats are all the same species, Felis catus or also seen as Felis domesticus. The species is the most prevalent domesticated animal in the Unites States, numbering between 148 – 188 million individuals. They are found on all 7 continents, with an estimated 600 million cats worldwide. House cats are those that are kept by a human family, but may be allowed to go outside on a regular basis. A stray cat is one that was owned by a human and was subsequently abandoned or lost. A feral cat is a domestic cat that has not been owned by a human, and as a result has become wild. Stray cats and young feral kittens that are adopted by humans may become socialized and make good pets; adult feral cats will not. Cats are very efficient predators, eating a variety of species of animals including frogs, salamanders, snakes, small mammals such as mice, and birds. Predation on native species is not limited to strays and feral cats; even house cats that are fed a healthy diet will kill wildlife. This is because cats often kill animals for practice, not for food. This behavior can be helpful, in the case of farm cats controlling rodent populations. However, in most situations cat predation in the environment is harmful to native species.

Environmental Impact

Stray and feral cats can have a detrimental impact on our wildlife. Domestic cats have great reproductive potential. Individuals become sexually mature as early as 6 months of age, and reproduction can occur throughout the year. A single female may produce as many as 3 litters each year with 2 to 4 kittens per litter, with the capacity to successfully raise as many as 12 offspring in any given year. With this potential to increase in population, the number of stray and feral cats in an environment can quickly overwhelm the natural resources by increasing competition with native predators and depleting populations of local prey species. Scientists estimate that 2.4 billion birds and 12.3 billion mammals are killed by free-roaming (house cats that are allowed outside, stray and feral) cats each year.

Free-roaming cats are also a cause for concern because of their ability to transmit diseases. They can transmit several diseases such as rabies, toxoplasmosis, cat scratch fever, typhus and feline immunodeficiency virus. Each of these diseases can have serious health implications when contracted by humans or local wildlife populations. For example, while comparatively very few cats have rabies many people that have contracted rabies have gotten it from exposure from a cat. Additionally, recent studies suggest that cats are responsible for transmitting toxoplasmosis to white-tailed deer. Furthermore, studies suggest that free-roaming cats may have transmitted feline leukemia to mountain lions and feline distemper to the endangered Florida Panther.

Management

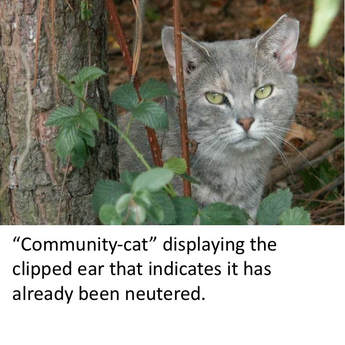

How to manage stray and feral cats in the United States is a matter of much debate. The Wildlife Society, the national organization of wildlife management professionals, supports euthanasia (humane death) of cats that cannot become adopted (i.e. they are too feral to become pets). On the other side of the argument, the Human Society strongly supports non-lethal population control of stray and feral cats wherever possible. Non-lethal control is usually conducted through a program called “Trap-Neuter-Release”, where animals are released back where they were trapped after they are neutered. Utah’s Animal Welfare Act contains provisions supporting “community cats” – those cats released back into the community after going through the Trap-Neuter-Release process. Much of the concern and opposition to any program that does not involve humane euthanasia rests on the fact that free-roaming cats are not native to any environment in the United States. Many scientific studies report that non-lethal programs do not reduce the number of feral cat in the environment. Additionally, releasing feral cats after sterilization does not mitigate risk of disease transmission or wildlife mortality caused by individual cats. Proponents of non-lethal control stress that a) it may be difficult to tell if the cat has an owner, and thus one might euthanize a pet and b) animals have a right to life, regardless of whether or not they are own. Put another way, humans created the situation for stray and feral cats and therefore it is our responsibility to treat them fairly. Proponents of all viewpoints advocate increased public education about how to care for house cats to reduce the number of pets that become stray and feral each year.

Andersen, M. C., B. J. Martin, and G. W. Roemer. 2004. Use of matrix population models to estimate the efficacy of euthanasia versus trap-neuter-return for management of free-roaming cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 225:1871–1876. Accessed at http://web.nmsu.edu/~groemer/JAVMA 041215.pdf

Barrows, P. L. 2004. Professional, ethical, and legal dilemmas of trap-neuter-release. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 225:1365–1369. Accessed athttps://www.avma.org/News/Journals/Collections/Documents/javma_225_9_1365.pdf

Scott R. Loss, Tom Will & Peter P. Marra. 2013. The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States. Nature Communications 4, Article number: 1396. Accessed at http://www.nature.com/ncomms/journal/v4/n1/full/ncomms2380.html

The Humane Society of the United States. 2013. The HSUS's Position on Cats -

A collaborative approach to giving all cats the best life possible. Accessed at http://www.humanesociety.org/animals/cats/facts/cat_statement.html

The Wildlife Society. 2011. Final Position Statement Feral and Free-ranging Cats. Accessed at http://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/28-Feral-Free-Ranging-Cats.pdf

The Wildlife Society Government Affairs. 2014. Study Finds Feral Cats Likely Driving Disease Among Deer. Accessed at http://wildlife.org/feral-cats-likely-driving-disease-among-deer-study-finds

Utah State Legislature. 2015. Community Cat Act. Accessed at http://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title11/Chapter46/11-46-P3.html?v=C11-46-P3_1800010118000101

Featured Animal: September 2015

By Dr. Nicki Frey

Stray Cats in Your Neighborhood

Each fall thousands of stray and feral cats begin to look for safe, warm homes for the winter; it is during this time that homeowners begin to see them around their homes more often. Not only can the outdoors be a harsh environment for a cat, cats can be detrimental to the environment. What to do with stray and feral cats in our towns is a divisive subject with some folks wanting to protect and sustain them with others supporting euthanasia (humane death). Because stray and feral cats are domesticated animals, their future is directly our responsibility.

House, stray and feral cats are all the same species, Felis catus or also seen as Felis domesticus. The species is the most prevalent domesticated animal in the Unites States, numbering between 148 – 188 million individuals. They are found on all 7 continents, with an estimated 600 million cats worldwide. House cats are those that are kept by a human family, but may be allowed to go outside on a regular basis. A stray cat is one that was owned by a human and was subsequently abandoned or lost. A feral cat is a domestic cat that has not been owned by a human, and as a result has become wild. Stray cats and young feral kittens that are adopted by humans may become socialized and make good pets; adult feral cats will not. Cats are very efficient predators, eating a variety of species of animals including frogs, salamanders, snakes, small mammals such as mice, and birds. Predation on native species is not limited to strays and feral cats; even house cats that are fed a healthy diet will kill wildlife. This is because cats often kill animals for practice, not for food. This behavior can be helpful, in the case of farm cats controlling rodent populations. However, in most situations cat predation in the environment is harmful to native species.

Environmental Impact

Stray and feral cats can have a detrimental impact on our wildlife. Domestic cats have great reproductive potential. Individuals become sexually mature as early as 6 months of age, and reproduction can occur throughout the year. A single female may produce as many as 3 litters each year with 2 to 4 kittens per litter, with the capacity to successfully raise as many as 12 offspring in any given year. With this potential to increase in population, the number of stray and feral cats in an environment can quickly overwhelm the natural resources by increasing competition with native predators and depleting populations of local prey species. Scientists estimate that 2.4 billion birds and 12.3 billion mammals are killed by free-roaming (house cats that are allowed outside, stray and feral) cats each year.

Free-roaming cats are also a cause for concern because of their ability to transmit diseases. They can transmit several diseases such as rabies, toxoplasmosis, cat scratch fever, typhus and feline immunodeficiency virus. Each of these diseases can have serious health implications when contracted by humans or local wildlife populations. For example, while comparatively very few cats have rabies many people that have contracted rabies have gotten it from exposure from a cat. Additionally, recent studies suggest that cats are responsible for transmitting toxoplasmosis to white-tailed deer. Furthermore, studies suggest that free-roaming cats may have transmitted feline leukemia to mountain lions and feline distemper to the endangered Florida Panther.

Management

How to manage stray and feral cats in the United States is a matter of much debate. The Wildlife Society, the national organization of wildlife management professionals, supports euthanasia (humane death) of cats that cannot become adopted (i.e. they are too feral to become pets). On the other side of the argument, the Human Society strongly supports non-lethal population control of stray and feral cats wherever possible. Non-lethal control is usually conducted through a program called “Trap-Neuter-Release”, where animals are released back where they were trapped after they are neutered. Utah’s Animal Welfare Act contains provisions supporting “community cats” – those cats released back into the community after going through the Trap-Neuter-Release process. Much of the concern and opposition to any program that does not involve humane euthanasia rests on the fact that free-roaming cats are not native to any environment in the United States. Many scientific studies report that non-lethal programs do not reduce the number of feral cat in the environment. Additionally, releasing feral cats after sterilization does not mitigate risk of disease transmission or wildlife mortality caused by individual cats. Proponents of non-lethal control stress that a) it may be difficult to tell if the cat has an owner, and thus one might euthanize a pet and b) animals have a right to life, regardless of whether or not they are own. Put another way, humans created the situation for stray and feral cats and therefore it is our responsibility to treat them fairly. Proponents of all viewpoints advocate increased public education about how to care for house cats to reduce the number of pets that become stray and feral each year.

- When you decide to own a cat as a pet, keep the cat as an indoor cat. Do not let it wander outside. They do not have to wander any farther than your backyard to impact wildlife populations.

- Once you’ve chosen a cat, or a neighborhood stray cat has chosen you, have the cat neutered. Especially if you don’t intend to keep it inside the house, or you find it impossible to keep it inside the house. Neutered pets tend to stay relatively close to the house, minimizing environmental impact and the chance that they may become strays.

- Have a microchip put in your pet so that it can be quickly returned to you if it does stray and is found by animal control officers.

- If you find a stray cat, please report it to your local animal control office so that it can be trapped and kept safe while providing its owners time to find it.

Andersen, M. C., B. J. Martin, and G. W. Roemer. 2004. Use of matrix population models to estimate the efficacy of euthanasia versus trap-neuter-return for management of free-roaming cats. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 225:1871–1876. Accessed at http://web.nmsu.edu/~groemer/JAVMA 041215.pdf

Barrows, P. L. 2004. Professional, ethical, and legal dilemmas of trap-neuter-release. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 225:1365–1369. Accessed athttps://www.avma.org/News/Journals/Collections/Documents/javma_225_9_1365.pdf

Scott R. Loss, Tom Will & Peter P. Marra. 2013. The impact of free-ranging domestic cats on wildlife of the United States. Nature Communications 4, Article number: 1396. Accessed at http://www.nature.com/ncomms/journal/v4/n1/full/ncomms2380.html

The Humane Society of the United States. 2013. The HSUS's Position on Cats -

A collaborative approach to giving all cats the best life possible. Accessed at http://www.humanesociety.org/animals/cats/facts/cat_statement.html

The Wildlife Society. 2011. Final Position Statement Feral and Free-ranging Cats. Accessed at http://wildlife.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/28-Feral-Free-Ranging-Cats.pdf

The Wildlife Society Government Affairs. 2014. Study Finds Feral Cats Likely Driving Disease Among Deer. Accessed at http://wildlife.org/feral-cats-likely-driving-disease-among-deer-study-finds

Utah State Legislature. 2015. Community Cat Act. Accessed at http://le.utah.gov/xcode/Title11/Chapter46/11-46-P3.html?v=C11-46-P3_1800010118000101